Artist Collection: Brian May’s AC30-powered Queen Backline Up Close

Granted exclusive access to Brian May’s stunning collection of Vox AC30s, G&B goes where no guitar mag has been before to find out what it takes to keep Brian’s amps operational on the road, why they’re now more reliable than ever and just why the Queen guitarist will never use anything else…

Story Simon Bradley | Photography Eleanor Jane

The Vox AC30 Twin, introduced in the spring of 1960, has its unmistakable tone all over the very beginnings of guitar-based popular music, and some of the greatest English bands ever have plied their trade through this most revered of combination amplifiers.

A band utterly synonymous with Vox are, of course, The Beatles, and the documentation of John Lennon’s first purchase of a Vox amp – an AC15 Twin bought on 27 July 1962 from Hessy’s Music in Liverpool – still exists. By early 1963, the band were well on their way to becoming the biggest band of all time and both Lennon and George Harrison had moved on to the classic black/brown AC30, with amps provided by Vox after manager Brian Epstein had reached an agreement with the Brit amp manufacturer. Paul McCartney also used an AC30 for a few shows around that time, albeit the head version called the Super Twin, fed into his trusty T-60 2×15 cabinet.

Rolling Stones guitarists Keith Richards and Brian Jones also used AC30s for a time after bassist Bill Wyman introduced them to his own Vox amp, as did both the Clapton and Beck incarnations of The Yardbirds; needless to say, the list goes on and on.

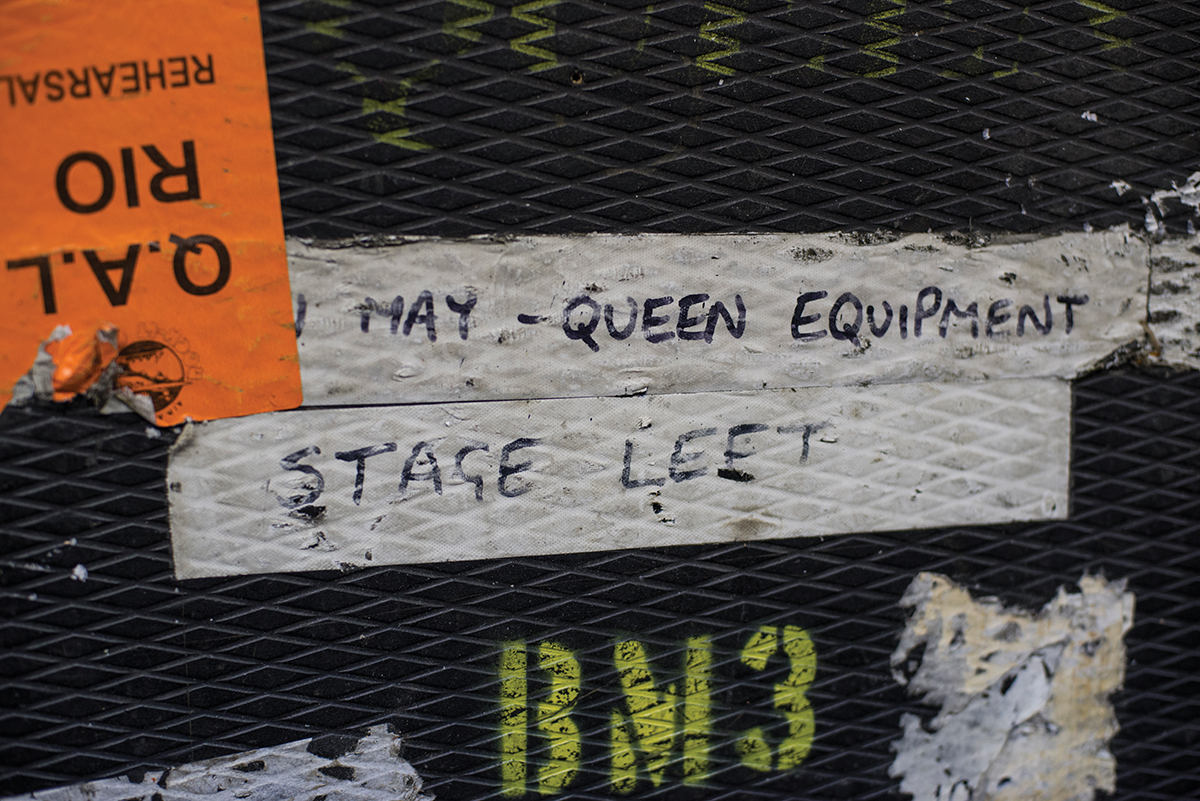

One of numerous road cases that have been around the world with Brian many times

The Beatles, the Stones and Jeff Beck were just some of the heroes an unassuming student named Brian Harold May looked up to. With assistance from his father, he’d spent 18 months building an electric guitar from scratch, one that would become known the world over as the Red Special. For amplification purposes, he had graduated to a Burns Orbit combo after years spent at home noodling through a Collaro tape deck’s preamp he’d plugged into a homemade radio.

May and his bands, first 1984 then Smile, were fitting in as many gigs around their academic studies as they could, but the young guitarist was growing concerned that he’d never achieve the sounds he had in his head.No stranger to the venues of the capital, Brian went to London’s Marquee Club one night, as he often did, little knowing that his quest for just the right tone was coming to an end.

May’s pedalboard is operated by Pete Malandrone from the side of the stage

“Hendrix was all about the guitar and the amplifier, and it had that sort of wonderfully smooth, almost orchestral distortion,” Brian told this writer in 2013. “I wondered how you did that, and the answer was actually given to me by Rory Gallagher. I used to go and see him every Thursday night at the Marquee and, after the gig, we’d sneak into the back rooms when everyone was leaving so we’d be able to see him.

“He was the nicest, most patient guy you could imagine. He told me about his guitar and a little box called a Rangemaster treble booster. He showed me his amps and said that he used the Vox amps because ‘…they just speak’.

“A bunch of us went down Tottenham Court Road to a second-hand amp shop called, I think, Take 5, and they had a few Vox AC30s, beaten up and all in a row.

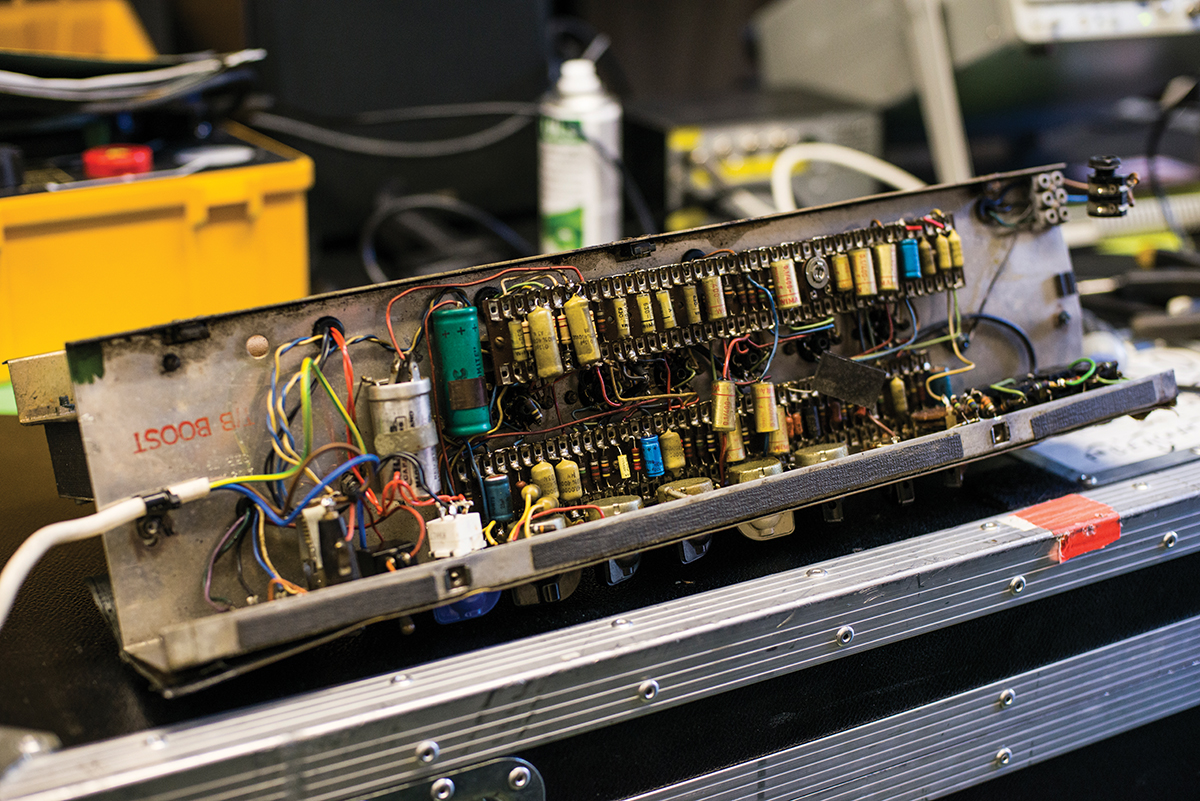

The chassis is eased from an AC30. “I tend to get them serviced more regularly than they need to be,” says Malandrone

“I plugged my Red Special and a Rangemaster that I’d found into one of these amps and the sound was just there. It had that depth, the overtones, the sustain, and the throaty splutter. I just knew that it was the sound I’d always been looking for, so we bought two at £25 each, took them home and that was it.”

So, is Brian May the most prominent exponent of the AC30 in music history? Well, that’s one of those eternally enthralling guitary questions, but we’d suggest he’s surely not far off. Put it this way: with numerous irons in the fire, he’s about as busy today as he’s ever been and, of course, neither The Shadows nor The Beatles are likely to be touring or recording any time soon.

Each of May’s main three AC30s is loaded with Celestion Alnico Blue and G12H Anniversary speakers. “Speakers have the biggest effect on an amplifier,” says Mike Hill

“He’s probably sold more amps for Vox than anybody else,” suggests Pete Malandrone, May’s long-serving guitar tech. “He recently bought a little Marshall valve combo for recording, just for something different, but he never actually used it. He tried Matchless for a while and also had, of all things, a Gallien-Krueger amp that was like a little suitcase [more than likely a GK 250ML – Ed]. But no, I’ve never really seen him use anything but an AC30.”

The current live backline comprises eight AC30s configured as follows: three are angled away from May, with the dry guitar signal running through the centre amp and the wet signal, courtesy of a TC Electronic G-Major 2 and a rackmount Dunlop Cry Baby, fed into the amps sat to its left and right. The trio immediately above them are on standby, ready to replace any of the main amps should they go down, and the final two of the octet are placed just offstage in case of dire emergencies. The top row incorporates three dummy AC30s that carry Malandrone’s stockpile of spare speakers, which explains why we actually see nine up there onstage.

May has been cranking out classic riffs and solos from his stage-left standpoint since 1970

It’s all go for Team May as full production rehearsals for Queen’s Summer Festival tour are imminent and, with Brian holed up in a recording studio somewhere, we’ve taken the chance to catch up with both Malandrone and engineer Mike Hill, who’s preparing to service the amps in readiness for the rigours of the road.

Hill cut his teeth at Marshall Amplification, joining the company in 1970 and, amongst many other achievements, developed the lauded JCM800 2203 head. Since setting up his own business in 1995, he has cultivated an enviable client list. We first ask him to describe exactly what the servicing of an AC30 entails.

“First, we check the earth’s on within the chassis and make sure that everything is mechanically solid, because obviously things do become loose over time,” he explains. “We remove any stray material before running it through the test gear.”

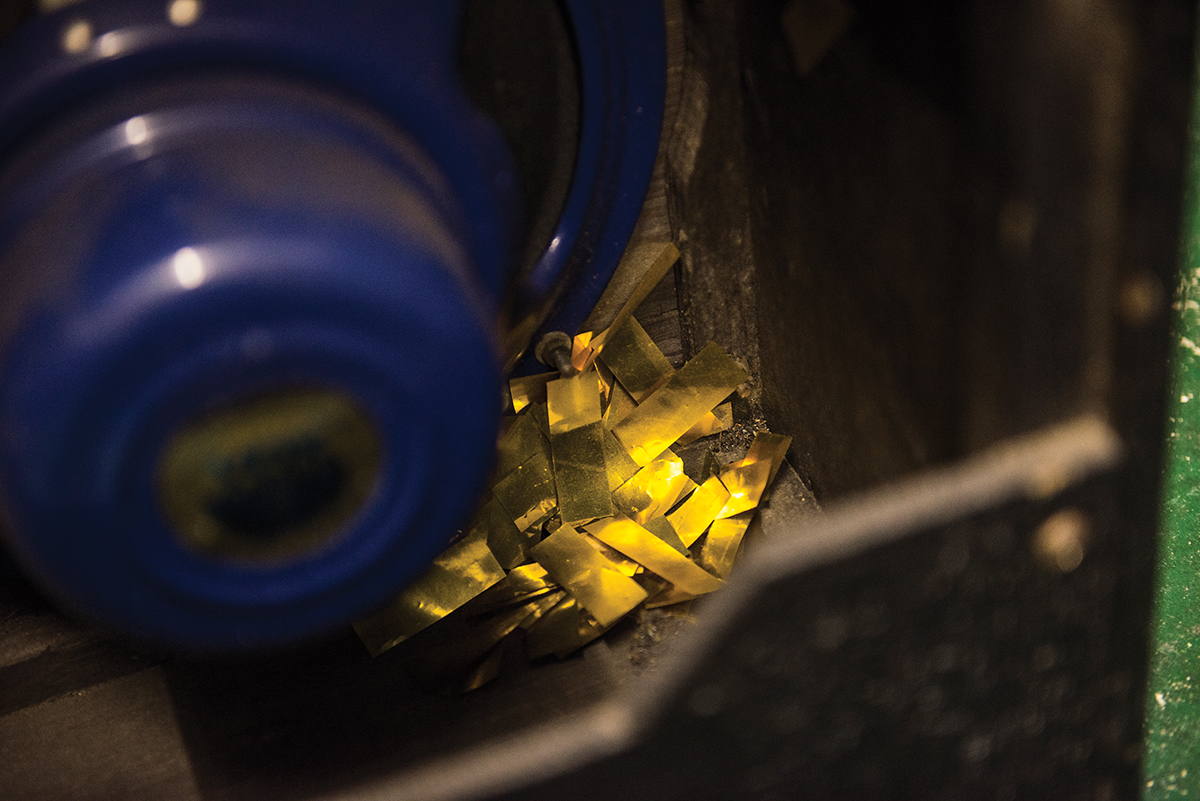

Amongst the stray material discovered in the amps being serviced today are strips of gold foil intrinsic to the confetti cannon finale at show’s end last time out.

Pete Malandrone, May’s guitar tech for the past 20 years

“When the cannons go off, I turn all the amps off and cross my fingers,” says Malandrone wryly as another potentially dangerous handful is retrieved from the recesses of an AC30’s chassis.

Hill, nodding sagely, peels yet another strip from the glass of an EL84 before continuing: “We check the fuses, then put in a 1k sine wave and monitor the output that’s driven into the correct load so the amp thinks it’s driving a speaker. Then we check all the controls and the valves, and ensure that the output level’s correct.”

We notice that the servicing didn’t seem to take too long, maybe a couple of hours to look over eight amps. A good sign, we assume.

“Well, if everything’s okay then there’s not really anything else to do other than ensure everything’s as it should be,” Hill reassures us. “Today, all that needed to be done fundamentally was to change four output valves that had actually worn out, which is amazing, as they normally break well before that stage.”

Mike Hill has been instrumental in keeping May’s amps operational for over 10 years

We’re quite surprised by this, considering how hard May runs his amps. The panacea for this long life is an unassuming piece of kit that lurks at the bottom of the live rack: a Kikusui PCR1000M power supply designed for the medical industry. Irrespective of where May is in the world, the unit will take the local mains and supply his backline with constant power at a voltage and frequency set by Malandrone. “Every amplifier has an optimum voltage that it requires, and in the case of an AC30 it’s 234V AC at 50Hz,” says Hill. “That generates all the correct voltages inside and, by giving it exactly what it was designed for, you get a really reliable situation. With these AC30s I’ve measured the voltages, that’s what we got and that’s what the power supply is set to.”

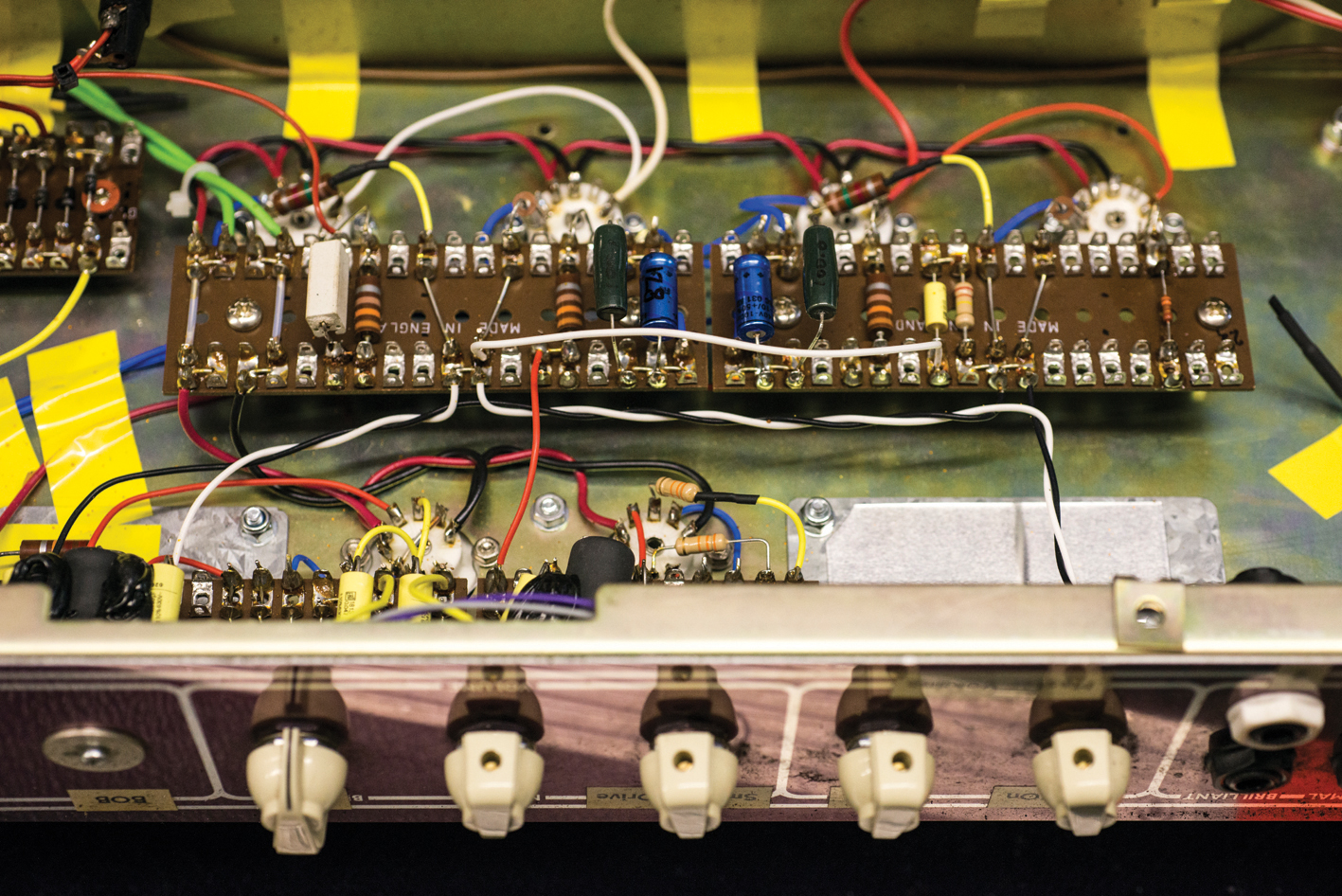

A detail of one of May’s main trio of AC30s, as initially modified by Australian engineer Greg Fryer for the We Will Rock You theatre show

Malandrone’s enamoured and, after telling us how much one of these units costs (clue: a lot!), continues to sing its praises. “It came along by accident, really,” he says. “On the first American Queen + Paul Rodgers tour [in 2006] we used a UPS [Uninterruptible Power Supply – Ed], which is basically a big battery that provides a stable voltage. We had Brian’s rig on one UPS and the rest of the backline on another, and I realised after we’d got home that we hadn’t had too many amps go down, maybe two or three during the entire tour. So, after speaking to people like Mike, I started looking at power supplies and found this. They’re expensive but well worth it.”

Hill monitors the output of each amp on an oscilloscope. “From experience, I know exactly what to expect,” he says

The Kikusui not only increases amp reliability, but also helps keep the sound constant, as Hill explains. “Because amplifiers have a very basic power supply, the frequency coming in is actually part of the signal, and if you drive the amplifier hard you can actually see it on the oscilloscope,” he says. “The power supply ripple, as we call it, is actually superimposed on the signal, and this means that if you play a note on the guitar there is an underlying set of frequencies going on. In the UK, these are multiples of 50Hz, starting off with a fundamental of 100Hz, and they modulate with the notes of the guitar. You can actually hear a 100Hz hum underneath the notes on some recordings from the 70s.

“However, in the States the frequency is at 60Hz, so you start off at 120Hz, then all the harmonics from 240Hz, 480Hz and so on. So the amp’s sound changes, and this is why it’s so important to have a fixed frequency for the amp system’s power supply.”

Hill removes yet another piece of foil, this time from an amp’s EL84 power valves. “They get everywhere,” he confirms

Each of May’s AC30s that see regular use has been modified to include just the Normal channel, which is controlled by a single volume knob. Virtually nothing remains of the other channels, save for some redundant chickenhead knobs, disconnected pots and input sockets.

Everything is point-to-point wired – no PCBs here – and, as can be seen from our pictures, is extremely neat and tidy. Reliability is the name of game, so much so that a solid-state rectifier, custom-made by Hill, has replaced the traditional GZ34 valve in all the amps, following in the footsteps of an operation undertaken on May’s amps back in the day by Pete Cornish.

“The first thing a valve does when it goes down is take the valve rectifier out,” stresses Malandrone. “The way that we came across the idea of using a transistor GZ34 was that Mike simply made one and asked me to try it. I plugged it in, Brian didn’t notice any difference in sound, and that was it. It just adds a little more reliability to the amp, and I’d defy anybody to A/B a GZ34 rectifier valve with one of Mike’s and tell the difference.”

How about the other tubes? “Valves!” exclaim Hill and Malandrone in tandem, quick to correct our inadvertent slip into Americana.

The Kikusui PCR1000M power supply. “It’s very light and robust, and doesn’t seem to go wrong,” says Pete

“There’s no absolute rule for the life of a valve,” says Hill. “With Brian’s amps, we match the valves so each one of a given specification is providing the same amount of bias current, and that’s about it. Hopefully, you’ll get a situation where, as here, they’ll wear out rather than fail.”

“On the last two tours, which was the best part of 60 gigs in Europe and America, I had just one amp failure,” agrees Malandrone. “I did some valve changes along the way because they do go dull, but these days I’m more likely to lose an amp to speaker failure than a valve flashing over.”

Talking of speakers, up until very recently there were different combinations in the three main stage AC30s. The centre amp was loaded with a pair of Alnico Blues, while both the left and right AC30s featured a Blue alongside a Celestion G12H Anniversary. Now, with an AC30 modified by Hill in the centre position, all three main AC30s feature a combination of the two speakers.

A chassis ready for testing. The yellow PAT tester checks for earth continuity, earth leakage and insulation

“What that does is give you a little bit of flexibility and reliability,” clarifies Malandrone. “If it’s the Blue that’s mic’d up and starts to sound a bit woolly, I can run on and move the mic over to the G12H. It’s the same gear every day, but Brian might not like how things are sounding because of the room or something, and it can be as simple as moving the mic across to make it sound better for that room.”

Among Malandrone’s many responsibilities while on the road is ensuring that the gear continues to operate during the continually humungous shows Queen are playing. We ask him to explain just what happens should an amp go down mid-show. He describes, almost nonchalantly, a process that, to us, resembles a Formula 1 pit stop.

An EL84 from Hill’s own Elite Valve series. Each is hand-selected and checked on a custom test rig

“You run onstage, throw the microphone out of the way, unplug the input jack and the power, move that amp out of the way, lift the replacement down, plug it in, take it off standby and put the mic in front of it,” he explains. “Then you go and get another amp and put it back in the middle row.” Fortunately, though, this is an increasingly uncommon happenstance.

The cornerstone of any AC30’s classic tone: a quartet of glowing EL84 power valves. Nothing sounds quite like it

“I’ve never gone through more than two in a show and, more recently, I can’t remember the last time an amp went down,” Malandrone goes on. “When I started with Brian, we’d be looking at an amp failure every couple of shows, and that’s down to me not having met the people I work with now. I didn’t really know anything about AC30s back then and I’ve learned things not only from my own observations, but by the process of getting to the bottom of certain problems, too.”

Imagine, then, being May’s guitar tech during the halcyon days of the 70s and 80s, when technology, not to mention health and safety constraints, weren’t anywhere close to the standards of today. At Queen’s absolute height, the amp setup was considerably larger and more complex, too, incorporating as many as 12 AC30s, all on and handling different signal feeds.

A drift of confetti-cannon foil in the corner of an AC30’s cabinet. Every amp on test was similarly embellished

“With no disrespect to previous employees, I know for a fact Brian used to be constantly worried about the gear,” says Malandrone. “When I first started he would always ask me if everything was all right: he never asks me now. It may well have been the case that, back then, they couldn’t source decent valves or there weren’t people like Mike they could go to for advice or help.”

So, does Brian get involved with the gear in any way other than playing through it? “No, not at all: he has little or no time or inclination now, and that’s the way it should be. He just needs to worry about what notes to play,” affirms Malandrone. “He leaves it to me and doesn’t worry unless he’s unhappy with how it sounds. Now, because it’s about as constant as we can get it, I can confidentially say to him that, aside from valve and speaker wear, nothing has changed between yesterday and today. Everything is always in exactly the same place and it’s always the same.”

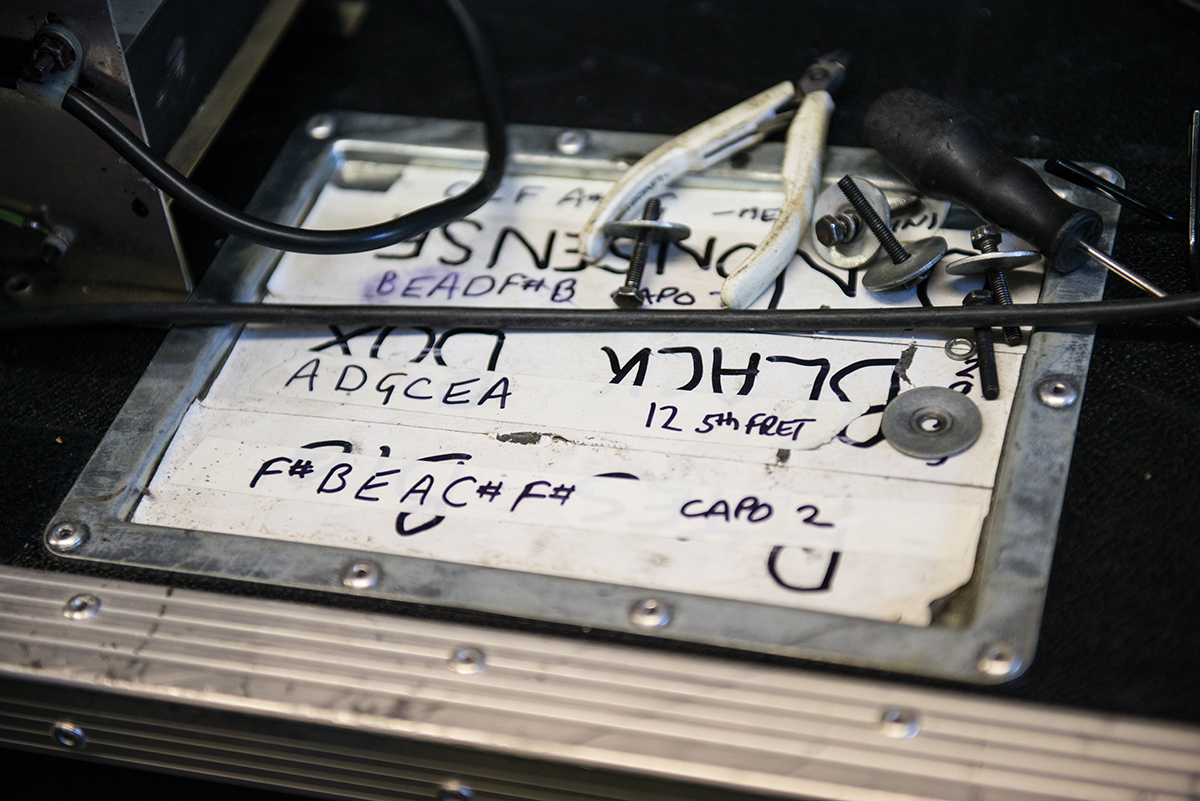

Amp-cabinet screws rub shoulders with tuning notes from previous gigs

So, the big question. What would have happened had the young Brian experienced his epiphany not thanks to Rory Gallagher’s AC30 but due to his biggest hero of all: Jimi Hendrix? “I’d imagine that it probably wouldn’t have made a massive amount of difference, and if Brian had started using Marshall heads, it probably would have worked just as well,” says Pete. “He’s so distinctive that he sounds like him whatever he’s playing through.

The three main Fryer AC30s, all serviced and ready to go. Each has only one operational control: the volume pot of its Normal channel

“You know, if he’d managed to get to talk to Hendrix or Clapton instead of Rory, he might have gone a different way, but I’m convinced that we’d probably still be sat in a big house in Surrey talking about it.”