Marshall Amps – The Complete History

The famous Marshall sound was founded upon an amplifier built in a garden shed by a few amateur radio fanatics, and the period until 1968 became the era of the first Marshalls – the classic JTM series. Rob Stockley tells the story of Marshall Amps…

London has no less than 800 blue plaques celebrating the birthplaces or former living quarters of famous men and women. They commemorate everything from dramatists to doctors yet, oddly, only two celebrate rock stars; one for Beatles John and George at the site of the Apple Boutique, and one at 23 Brook Street in Mayfair, the one-time pad of James Marshall Hendrix.

In 2012, however, another plaque went up on the wall of 76 Uxbridge Road, Hanwell, west London. It wasn’t blue, but black, and it was placed on a site very much connected to the legacy not only of Hendrix but of thousands of other artists as well. Back in the early 1960s, number 76 was the shop where the first Marshall-branded amplifier was sold. Just 11 feet wide and 22 feet deep, these tiny premises marked the first step in a journey that would lead to another shop, then a series of workshops and factories, ending with the large, modern facility of today in Bletchley: to several Queen’s Awards For Export, a turnover of goodness knows what and, of course, a worldwide reputation amongst players of all ages for righteous-sounding amplifiers.

Jim Marshall, who passed away in April 2012, began his career as a danceband drummer and drum tutor. He saved his money and opened his shop at number 76 in July 1960, first selling just drum kits, then the expensive imported band equipment his customers wanted, such as Gibson 335s, Fender Strats and Fender Tremoluxes.

However, Fender amps just weren’t coming in fast enough, and they were expensive. This left a huge hole in the development of the UK’s rock scene, and it was a hole that home-grown products such as the Dominator amp, the Bird Golden Eagle and even the lauded Vox AC30 struggled to fill. Bass gear in particular was near-unobtainable in the very early ’60s (Bill Wyman, it’s said, gained entrance to the Rolling Stones partly on the strength of him possessing a huge homemade bass cab).

Jim Marshall’s first step towards his destiny came by building cabinets containing Goodmans speakers for the only half-suitable standalone valve amps you could get hold of in Britain at the time, first Linear amps, then 25W Leaks. These cabinets weren’t built at number 76, Jim reported – there just wasn’t any space – but at his home on Sundays.

First Steps

Half a century is a long time, and the exact details of the development of the guitar amplifier that would become known as the first-ever Marshall are subject to some somewhat differing opinions. The official Marshall tale is consistent and often-repeated. In 1962, the story goes, Ken Bran – recently employed by Jim as an amp repairer – made a suggestion that buying so many amplifiers didn’t make sense when the resources could be assembled to produce their own.

Regular Marshall customers such as session player Big Jim Sullivan, the Tremoloes’ Brian Poole and youngsters like the High Numbers’ Pete Townshend were all in agreement: an amp like a Fender, but cheaper, with guts, would sell very well indeed. No doubt, Jim’s astute business brain must have thought of the success of Tom Jennings’ Vox company, situated a few miles down the Thames on the other side of London. In 1958 Dick Denny had come up with the unique-sounding AC15 amplifier; now, a mere four years later, Vox had won the priceless patronage of the most popular group in the country, the Shadows. Could Ken Bran draw up an amp that could make a similar impact? No, but he knew someone who certainly could. And so an ex-BBC electronics whizz called Dudley Craven joined the team.

It’s worth considering the subtly different tale related by Ken Underwood, writing on the Vintage Amps Forum. The story, says Underwood, was that before any Marshall involvement, Dudley Craven formed a partnership with one Richard ‘Dick’ Findlay. Findlay performed in an advisory role but didn’t want to be officially involved. Ken Bran was next to come on board. It does seem that Bran and Craven worked together on the all-important technical side of the first amps; Ken Underwood himself took part slightly later, from early ’63 to late ’63, helping out on mounting the main mechanical components to the chassis.

Marshall lore has it that the first ‘complete’ Marshall amp, the famous bare chassis, was demonstrated in the shop at number 76 in the autumn of 1962, where it caused a sensation – plus a flood, according to Jim, of 20 or more immediate orders – and was sold to Pete Townshend. Interestingly, photos of the pre-Who High Numbers – a fairly well-documented band – show it was John Entwistle who was using a JTM45 around 1964-’65, plus what’s claimed to be the first-ever Marshall 4×12”, while Pete was still using a blonde Fender head with two Marshall cabs stacked beneath (one of which was a dummy).

Ken Underwood says that the first amp – Marshall, or Craven/Findlay? – was tested one Sunday night at nearby music venue The Ealing Club by a local group of musicians who always gave useful feedback when it came to the all-important matter of the sound. Underwood says he remembers the line-up of the band on the first test date – future Jimi Hendrix Experience drummer Mitch Mitchell (who was either employed or just about to be employed by Jim Marshall as a ‘Saturday boy’ in the shop), Dave Golding on sax, Kenny Rankin on bass and Jimmy Royal on lead and vocals. The band, Underwood says, played several numbers including Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah and, crucially, a cover of the recent Beatles hit I Saw Her Standing There – which was not released in 1962 at all, but on 22 March 1963.

Confusing? No doubt… and there are other versions of the story too – such as the testimony of Ken Flett, who joined the Marshall operation in 1963. According to Flett, the genesis of the idea for a Marshall amp lay with Jim’s son Terry Marshall and also with Mick Borer, who worked in the shop (incidentally, Terry and Mick would both leave Jim Marshall’s operation at the same time, in 1968 – at which point the ‘JTM’ designation for ‘Jim and Terry Marshall’ would abruptly be changed to ‘JMP’ for ‘Jim Marshall Products’ – and later joined forces with Simms-Watts amplifiers based in nearby Ealing). Terry Marshall has also said that he was present at the first trial of the prototype amp, that he was playing sax in the Ealing Club band, and that he also remembers the guitars that were used that day… a Strat and a Gibson 335.

The very first amplifiers – a run of six, most parties agree – were not built on Marshall premises, since at number 76, the tiny shop with a counter down one side and drums piled on shelves to save space, there was simply no room. Instead, they were assembled in the builders’ sheds at home, and – according to Underwood – sold by Marshall through the shop on a commission basis. And then Jim Marshall astutely took control, employing Dudley Craven and Ken Bran officially on the amp-building side, adding his own name, selling the new ‘Marshall’ amps exclusively through his shop and taking control over the cabinet-building and all the vinyl work in the rear of a new, larger premises just across the road, at number 97.

Bassman Inspiration

The amplifier that we can assume Dudley Craven created with the help of Ken Bran was modelled fairly closely on Fender’s Bassman combo, the 1959 version, now considered to be one of the finest-sounding guitar amps of all time. Of course, there were small but telling differences both within the circuit and without, and to what degree these were intended to circumvent any possible copyright or were purposely chosen to reflect the tonal tastes of the main designer, Dudley Craven – not to mention the players who test-drove the earliest models – is a matter of conjecture.

However, everyone agrees that the new amp was not intended to exactly ape the Bassman, but to better it. ‘Like a Fender, but more so’ was the aim, and the Marshall-to-be certainly succeeded. It was loud – louder, for sure, than an AC30. It was also fiercer, edgier and more raucous than the Fender, yet it was rich and sweet. Plugged into the ‘high’ input of the normal channel, the guitar sounded tonefully smooth; swapped to the brilliant side, the result was ear-slicingly sharp and trebly. Most of all, the quality of the sound was fantastic.

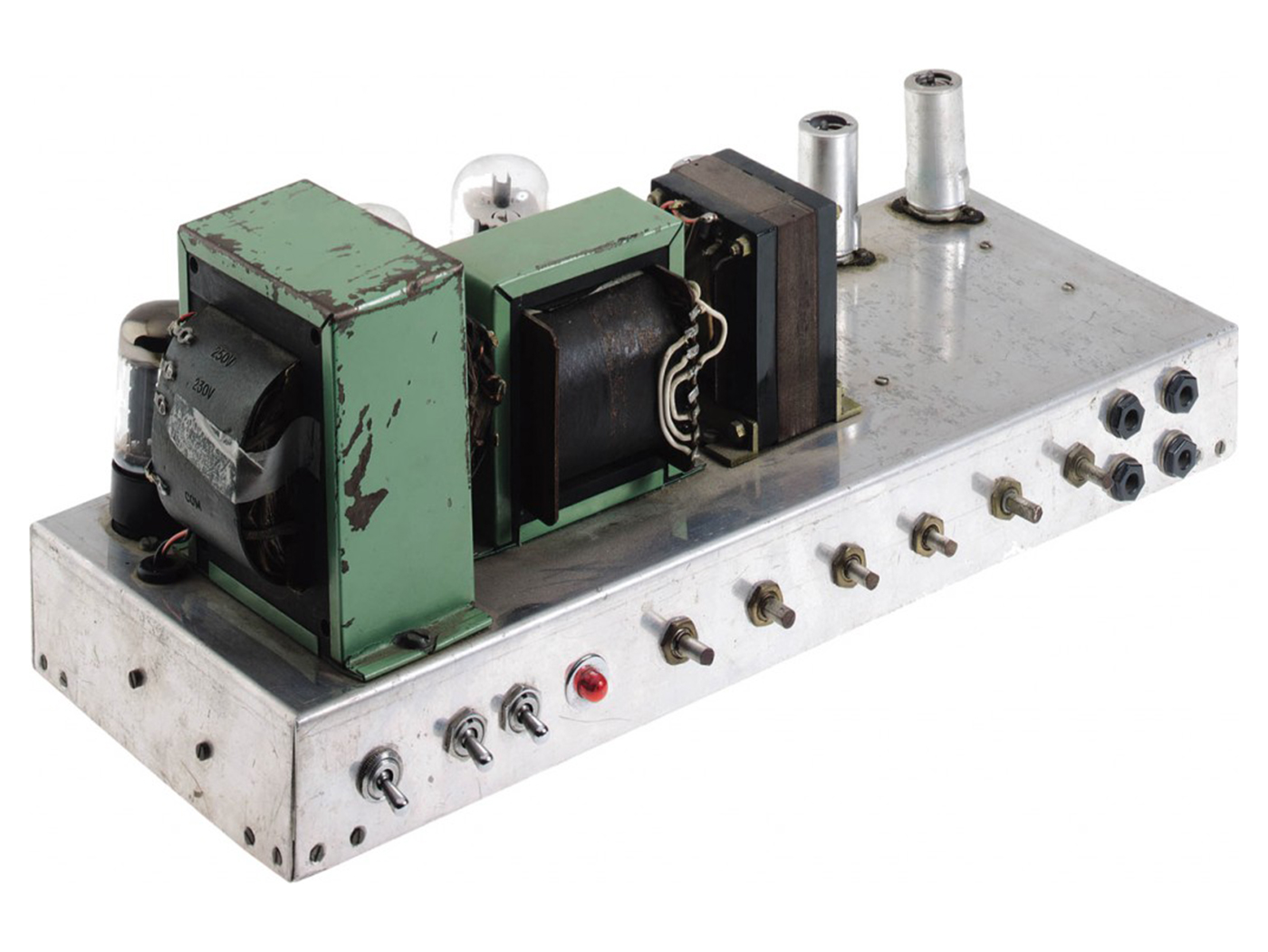

The differences in the sound between the Fender 5F6A circuit and the new amp were bought about both by component choice and component availability. The all-important first valve in the preamp stage in the Fender was a 12AT7; the UK amp used a ‘gainier’ 12AX7. The output valves were essentially the same – Fender used 6L6s, and so did the new amp – but before long, Marshall’s shift to big-bottled Mullard KT66 power valves would accentuate its British accent still further. Where Fender used US-made Triad brand transformers, the Marshall’s naturally UK-sourced Radio Spares mains and output transformers had a distinct effect on the various voltages and impedances within the amp (the Marshall ‘prototype’ in the company’s museum has Elstone transformers, a sign of just how much the spec of the early amps was down to trial and error). On top of that, the early UK amps had a folded aluminium chassis in place of Fender’s stronger steel version. Non-magnetic aluminium doesn’t affect the transformer’s magnetic field in the same way as a steel chassis, but it’s a better conductor than steel. Some say an aluminium chassis gives a faster response and better high end.

There were other design changes, too. The negative feedback circuit on what was to become the JTM45 used a different tap from the output transformer – an apparently small but tonally very telling change – while various bright capacitor changes contributed their own flavour. These alterations all gave the new amp a new and distinct sound. But perhaps the biggest difference between the Bassman and the Marshall would be the speakers and the cabinet. The Fender had four US-made 10″ Jensens in an open-backed cabinet: after initial experiments with two 12″ speakers, all lead or bass model Marshalls came with Jim’s personal brainchild of four 12″s in a closed cabinet. This sealed cab allowed the use of sensitive Celestions – the spec changing from 15W to 20W apiece, and finally to 25W – with the sealed cushion of air inside the cab preventing the cones blowing at peak watts… mostly.

From JTM45 to JTM45/100

It’s interesting to see how much the cosmetics of early Marshalls changed over the next three years. The very first examples – stubby-looking things by modern standards – came covered in smooth black leatherette, with an all-blonde front to match the speaker cab grilles. The oddest thing about the first few amps was the way the chassis was stuffed up at one end of the cabinet to make sure the amps balanced properly when carried, but the result was a very lop-sided affair. Marshall says that only three of these ‘offset’ amps were made. Rather like pieces of the ‘true cross’ there are almost certainly more than this in circulation on the vintage market, for alas early Marshall amplifiers – and indeed later ones too – have long been a target for unscrupulous fakers.

The ‘offset’ amps and the amps that followed soon afterwards all featured small, ornate metal nameplates with ‘Marshall’ in red enamel, specially bought from Butler’s in Birmingham – a funeral hardware supplier, hence today’s nickname, ‘coffin badges’. Jim Marshall was quoted a number of times as saying that only ‘a hundred or so’ were ever ordered, and some amp reference books – Aspen Pittman’s Tube Amp Book and Ritchie Flieger’s Amps – The Other Half Of Rock’n’Roll – agreed, which implied that since the guitar, bass and PA cabs also came fully badged, the number of metal-badged JTM45s must be less than 50. This is not correct, however, and other estimates put the number of metal-badge amplifiers at 500 or more

Around the same time that Jim Marshall took out a lease on the slightly larger shop at number 97 situated across the street and began using it for the cabinetry and the cloth and vinyl work, the amp cabinets became physically longer and the ‘double thickness’ look of the originals’ front edges was dropped. The colour scheme was still black with an all-blonde front, but both the metal nameplate and the entire chassis was now placed centrally in the cabinet. Internally, there soon came a shift from aluminium chassis to steel; the early chassis had trouble bearing the weight of the transformers, hence the change to a stronger metal.

Before long the all-blonde fronts were changed to a new black/blonde two-tone livery, sometimes nicknamed today the ‘sandwich front’. At this stage the control panel still bore no ‘JTM45’ designation and had distinctively closely-spaced input jacks plus a polarity switch, but a new consignment of shiny aluminium control panels was soon ordered, bearing the now-familiar legends ‘Mk II’ and ‘JTM45’ (the ‘45’ figure was plucked out of the air, since the RS De Luxe output transistor was rated at 30W). And there was more than just a guitar amp in the early catalogue: there was also a PA version and a ‘bass and lead’ version (which had the first valve wired in common cathode mode, plus about four slight component differences over the lead model), both priced the same, at 60 guineas. The 4×12″ lead guitar cab cost 15 guineas more than the amp.

By the end of 1963 it was apparent that the over-the-road operation at number 97 wasn’t enough, so cabinet production moved to a 20-by-30 foot shed a mile or so up the road in Southall. The two-tone amp design was dropped, replaced by the all-black livery that has graced backlines ever since, but the logo went through two reincarnations in the old upright lettering – first red letters on a large silver perspex rectangle, then black on gold – before the now-familiar Marshall ‘script’ logo made its debut in 1965. The control panels changed to suit, first a white-backed perspex then, in ’65, gold perspex – the famous ‘plexi panel’.

By this time all manufacturing had shifted from Hanwell to a workshop at 28-30 Silverdale Road, Hayes, Middlesex, giving a much greater capacity and the opportunity to introduce some new models. First came the model 1962 combo, essentially a JTM45 packaged with two Celestions, an amp now forever known as the ‘Bluesbreaker’ amp thanks to Eric Clapton’s epic use of it on the John Mayall With Eric Clapton ‘Beano’ LP.

Secondly, in late 1965, came the amp that finally solved Pete Townshend’s volume problems and paved the way for ’70s rock, made simply by taking a standard 50W box and doubling the number of output valves and using two valve rectifiers and two JTM45 output transformers. This, the ‘JTM45/100’, was the forerunner of the modern 100W Marshall. By now, the provision of two 4×12″ cabs on top of each other – a terrifying vision at nearly seven feet in height – was becoming increasingly commonplace. Townshend had asked for a monster 8×12″ cabinet, but his roadies wisely advised that splitting the monster in two would be a much better idea.

Marshall Takes Off

The JTM45 amplifier arrived just before the onset of a new wave in popular music. The first Marshalls were sold to a wide variety of busy bands: Brian Poole and the Tremolos, local outfit The Army, Eden Kane, Screaming Lord Sutch… even the odd Irish showband. But that mixed demographic was about get an injection of rougher, more basic blues-based music, a heavy R&B blasting out of London and the south, and by 1966 the Marshall catalogue boasted such names as the Spencer Davis Group, the Yardbirds, the Graham Bond Organisation, the Action and the Small Faces. For a hip guitar player seeking a great proto-rock sound in ’65, ’66 or ’67, a Marshall was a perfect option.

As well as Pete Townshend and The Who, the name who perhaps most helped Marshall was Eric Clapton, the first to discover the incredible noise a Marshall made when dialled to 10 and fed a Gibson Les Paul (to the great distress of the recording engineer). Word spread fast. Jimi Hendrix was a loose cannon in London in late 1966, creating havoc by tearing up any guest-spot he could grab; surely prompted by his new drummer Mitch Mitchell, Jimi visited Hanwell in mid-October and bought three 100W stacks.

Although Vox was still keeping pace at this time – the AC80/100 and AC100 had a user list far greater than Marshall’s, including such names as the Beatles, the Stones, Herman’s Hermits, the Hollies, the Pirates, the Move, Procul Harem and many others – they would soon move too early into transistor technology, leaving Marshall to take valve-driven sound forwards. Cream, Led Zeppelin and most of the second wave of British rock bands would all carry the word to the US in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

Crucially, the JTM45 had taken inspiration from a great Fender tweed amp at the very moment that Fender was moving away from that sound. For Fender, the period 1962-’64 was the ‘blonde’ and ‘brownface’ era, a time of much experimentation where drastic circuit alterations would soon lead to the bright but relatively calm and controlled ‘blackface’ family of amps of the mid-’60s. What Dudley Craven and the other wizards behind the early Marshall amps had done was to grab a ’50s tweed circuit that was outdated in Fender’s eyes, shake it by the scruff of the neck and send it spinning off in a new, raucous direction – a direction that became the sound of British rock.