“They are totally meant to be turned up!”: Amp-maker Phil Jamison on Matchless amplifiers

Don’t talk to Phil Jamison about the supposed magical ‘eras’ of Matchless amplifiers, thank you very much. They have all been great, and there’s evidence the California maker is building them better than ever.

Plenty of small-shop amplifier manufacturers have laid claim over the years to having started the ‘boutique’ phenomenon. Few guitarists who swim in those warm, sultry waters wouldn’t argue, however, that Matchless was the biggest fish of the boutique revival of the 1990s and 2000s, and still represents the epitome of the breed for quality of construction, roadworthiness, and ungodly giggable tone, too.

Much has been made of Mark Sampson’s role with Matchless, from the co-founding of the company, to the design contributions, to the eventual decline and bankruptcy in 1999. But if there’s a steady hand we can credit with reinvigorating the company and guiding the brand back to its place atop the hand-wired heap, it’s that of Phil Jamison, Matchless’ Chief Operating Officer and 21st century visionary – and just an all-round good guy, by any standards.

California dreamin’

Jamison was born and raised in Spring, Texas, which he recalls as “a great place to grow up.” He came to the guitar early, and long before he would discover an apparently innate knack with valve amps, he fully intended to forge a career with the instrument when the time came to leave the nest.

“I started playing guitar when I was nine,” he recalls. “I taught myself. I took my step-dad’s nylon guitar, made by Gibson, and a Bob Seger songbook and a Bob Seger record, and just followed the pictures, and voila! I moved from Texas when I was 18, directly out of high school, and went to Hollywood and enrolled in the Musician’s Institute. I did the G.I.T. [Guitar Institute of Technology] programme, and stayed in California ever since.”

Advertised in the back pages of prominent American guitar magazines in the 1980s – with ‘class’ photos showing the stars you’d purportedly rub elbows with, and (so it was implied) receive instruction from – G.I.T. was many a young hopeful’s embodiment of the California dream. And although it did set Jamison on a trajectory that has landed him where he is today, the reality was not at first quite so shiny as the glossy spreads themselves.

“The way the ads were, and the catalogue, it made it seem like these huge A-list people were always there, kinda’ hanging around. But if and when those guys even went there it would be like…one time.”

After attending the Musician’s Institute, Jamison took a job with a cartage company, hauling gear for prominent musicians on the LA scene, and from there segued into a job with the amp company VHT in 1991, which was then still owned by Steven Fryette. Prior to that gig, Jamison’s experience inside tube amps had consisted solely of working on his own gear, but the stint with Fryette provided a great launchpad into the formalities of the amp business.

“Stevie is a super-brilliant guy,” says Jamison. “A fantastic engineer, and guitarist as well. He’s really good. He taught me a lot. Their method of building was radically different from Matchless, which was fine. But there was still plenty of wiring in there, so I was able to learn to do all of that. It was an easy transition when I went into Matchless. When you do a job like that, and the way things were set up, they immediately put me into wiring and sat me at a table.”

A matchless opportunity

Jamison started with Matchless in late 1992, just three years after the company was founded, where he worked his way up from the ground floor.

“I was doing all the QC,” he relates. “I trained most of the line workers, taught them how to build amps. I built all of the prototypes. Amps like the [John] Jorgenson and the Chief, I had to completely build those from scratch. So basically, with the Jorgenson, Mark [Sampson] walked in and said, ‘Hey, we want to build an amp for John. It’s got to have an EF86 circuit, and it needs tremolo and reverb. Come get me when you get stuck.’ And that was how that happened.

“I built the first four or five of those, and one of them was pretty cool. I had to cut the chassis to do it, but it had two 15-watt output transformers outside and one 30-watt power transformer, and then I built two separate tremolo circuits, so it had a dual tremolo thing going. One output transformer went to two 8-inch speakers, and the other went to a 12. It had kind of an interesting sound to it. There’s only one in the world. I don’t know if John even still has it, but that was built specifically for him.”

As the late 90s approached, however, Matchless hit several bumps in the road. Turbulence caused by over-expansion and, apparently, the knock-on effect of the recession in Japan ate away at the business. Jamison was a victim of the first round of layoffs at the company in 1997, and Matchless itself went bankrupt in 1998. Meanwhile, Jamison found work here and there around LA’s bustling boutique amp scene – even consulting at TopHat for a time – until the opportunity came to help get the leading brand in genuine point-to-point manufacturing back on its feet.

“We reopened in August of 2000,” says Jamison, “when I came in as Chief Operating Officer, and I’ve been running all the operations ever since.”

Getting to the point-to-point

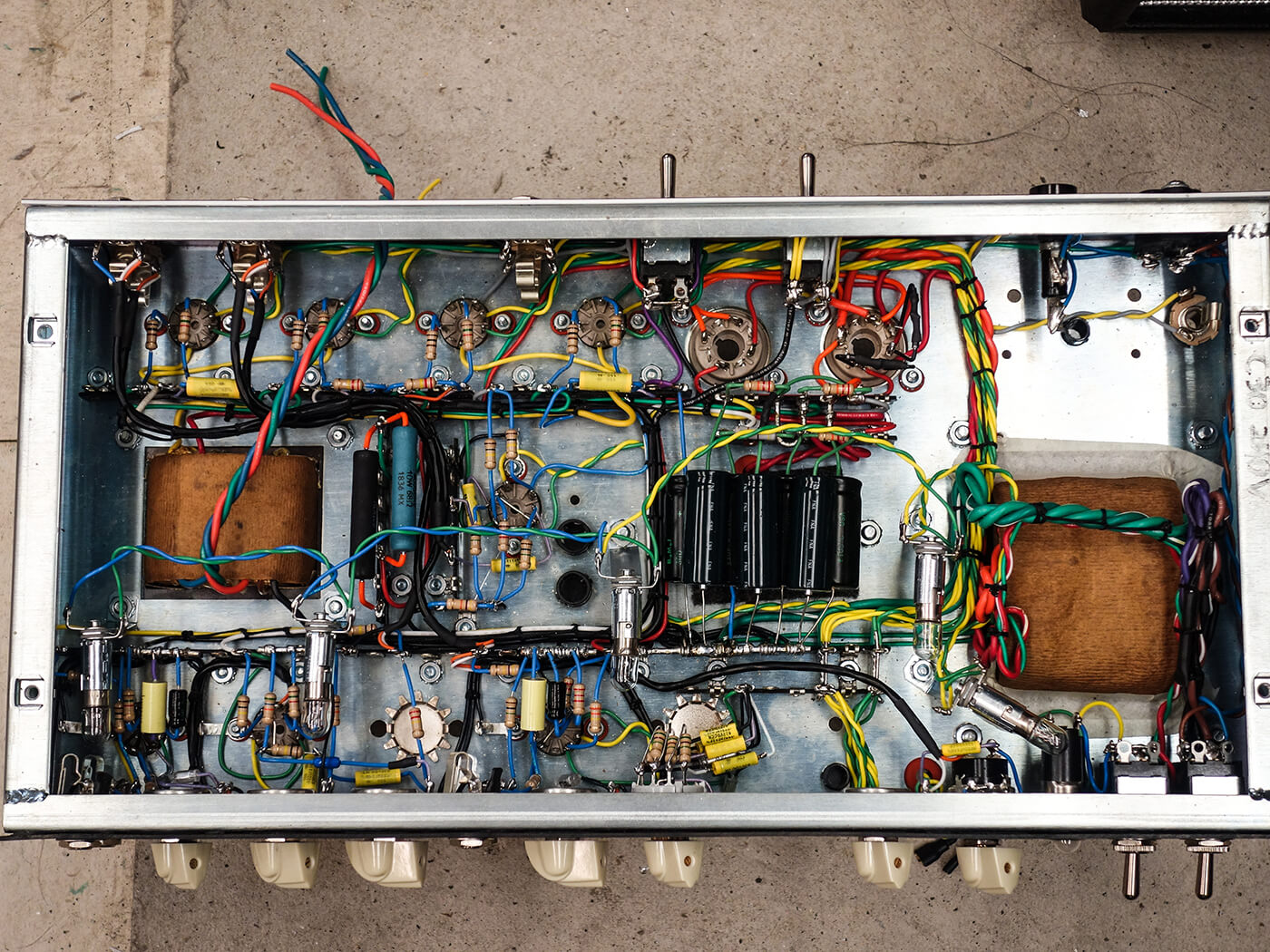

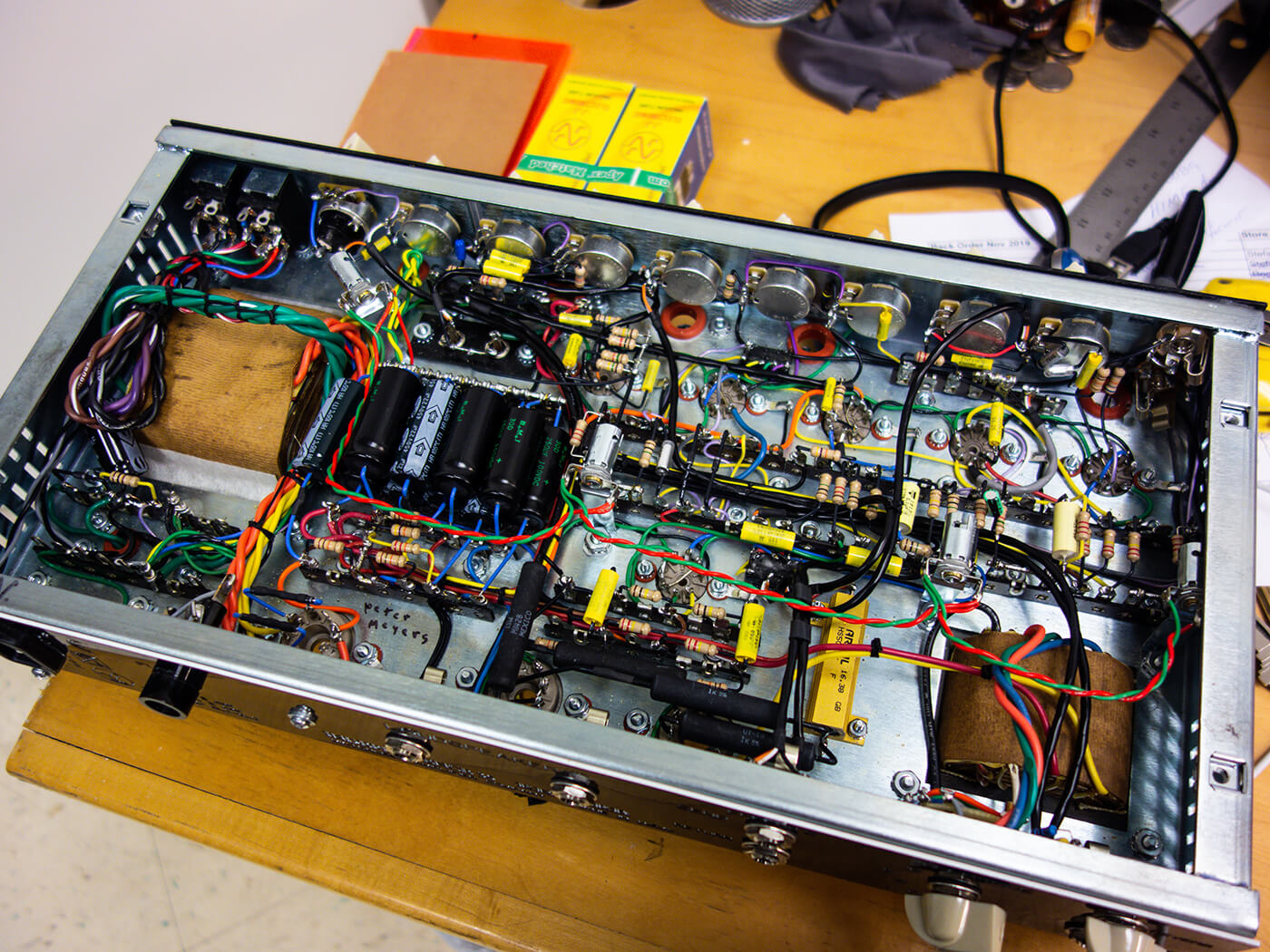

If guitarists recognise the Matchless brand for its overbuilt construction quality and robust tone, any solder junkies within earshot of the name’s mention will snap immediately to the painstaking wiring jobs inside these amplifiers’ chassis.

Makers using any form of hand-wired circuitry will often promote their work as ‘point-to-point’, but that term is more accurately reserved for chassis in which components are connected from one stage in the signal chain to the next largely with the use of other components: a resistor’s own leads connect the input jack to the first preamp valve socket, for example, and a coupling capacitor connects the output of that gain stage to the volume potentiometer, and so on.

This is how Matchless amps are made – how they were from the start, and how they continue to be manufactured to this day – with just a short terminal strip here and there for component support, and no actual ‘circuit board’ as such.

“It’s difficult to do only point-to-point,” Jamison relates. “It’s super expensive to do it that way. We see some other brands out there where they’re not doing point-to-point, and they’re sort of trying to undercut what we’re doing. And sometimes the customers don’t necessarily understand or see why one thing is $4,000 and another thing is $1,000. It doesn’t really register, the kind of quality that they’re getting.

“The most I see of it is some of the comments on the forums. I think some people don’t appreciate or understand what it fully takes to build something like this from scratch, and all of the factors involved.”

He adds: “And there are so many factors that play into what makes an amp sound good, that it’s not just one magic thing. I mean, just because you’re doing a point-to-point amp doesn’t mean it’s going to sound better over something else. You need the right metals, the right thickness of the metal, the transformers, and oftentimes the types of parts you use play such a huge factor in the overall thing. There’s no one magic bullet that’s like, ‘Oh, if I put /this/ ingredient in it’s going to be perfect!’”

Total transformation

Although, as Jamison attests, there might be no single magic component responsible for that lively, dynamic, expressive Matchless tone – which is to say, every component is critical in its own way – he will point to one large part that constitutes the humming heart of the operation.

“The most important thing,” says Jamison, “is the transformers. Our transformers are crazy expensive. I would say the cost of them is probably quadruple of what most other transformers are, but there’s a reason for that. And then the chassis, the actual metal, plays a big difference in sound. I’ve experimented a lot with thinner chassis, thicker chassis, chassis made of aluminum… all of those things really do play a huge factor in sound and clarity.

“And then, you’ve got the specific parts that you’re putting in, makes a big difference. And layout of that makes a very big difference as well: you can actually have the circuit wired in one way that won’t sound as good if you wire it in a different way, if you lay stuff out in a different area. I’ve found I can lay parts in different directions and the field hum just immediately cancels out, like a phase relation.”

While any amp enthusiast versed in Matchless builds both old and new will tell you that the company really does make them just as good as it ever did, employing the same methods, and components that are the same or at least as close to the originals as are currently available, it’s interesting to hear that Jamison has used his solid 20-year tenure with the reinvigorated manufacturer to actually improve upon the results.

Among other things, his own thorough re-layout of the circuit of the C30 – the circuit configuration in company’s flagship DC 2×12 combo, SC30 1×12 combo, and HC30 head, and still its all-time best seller – has yielded an amp that is notably quieter than before, while retaining every ounce of the cut, bite, harmonic sparkle, and touch sensitivity which has made the model famous since 1989.

As a bonus, Jamison says, “with completely revamping the C30 chassis I’m able to do much more stuff; I can do tremolo and reverb, and multiple channels. I’ve also changed the effects loop on those things… There used to be one TRS jack [per channel], but by revamping the entire rear control panel I did a separate 1/4-inch send and return for each channel, and people seem to like that a whole lot more than having to find a stereo-Y cord to use the loop.”

Without getting into the semantical quagmire that so many sellers of older used Matchless amps have employed to give their listings a boost, the continual push by Jamison to make a great design better kinda’ does put paid to that whole ‘Sampson-era’ tag that re-sellers like to hang from their creations from the ’90s.

Made for the stage

Other than gripes about price from players who might not appreciate what goes into these creations, and the results that such quality delivers, guitar-amp chat rooms on the web will sometimes cough up threads from users who find Matchless amps too ‘hard’ or ‘punchy’ sounding, or just ‘too damn loud!’ Almost universally, however, these are misfires of application, rather than of performance on the part of the amps themselves.

Which is to say, guitarists who purchase these things to use solely in their garages, bedrooms, and basements sometimes just don’t… get it.

“There’s definitely the higher-end pros, the actual working people that I deal with, they certainly get it,” says Jamison. “Just completely. And there’s never even a flinch or a hesitation on anything. They fully understand what they’re getting and how it impacts their sound. Whether it’s the touch response, or how it cuts through. Where it sits in the mix when they’re playing in a live situation or the studio. All those factors, all those little tiny nuances. They hear it, and they get it.

“It’s important for an amp to project. There’s times when you hear an amp by itself in a room and it sounds great, but then you get it into a large room or with a band or whatever and you realize the amp really only projects two or three feet, and after that it just falls apart and becomes mud. And that projection is a hard thing to achieve.

“If you’re using one of our amps trying to get the bedroom rockstar thing going, well, they’re not made for that. That’s the thing about these amps: they are totally meant to be turned up. That’s part of the magic and the sound and the ambience that they really kick off. These were meant for the stages and the studios, and to be played in that sweet-spot, volume-wise.”

While early classics like the DC30 and the 15-watt Lightning might remain company flagships, several of Jamison’s own designs of the latter era have won plenty of fans, too. The three-channel Independence, the DC30-meets-EL34 Phoenix, and the Avalon (“one of my most favorite amps I’ve ever designed. They just sound completely incredible!”) have all helped to push the envelope for the premier maker of point-to-point valve architecture, and there’s another brand-new creation for which Jamison also has high hopes: the Laurel Canyon.

“It’s our very first 6V6 amp,” he explains. “I’ve done a 20-watt version with two 6V6s, and I just built our first 40-watt with four of them. It’s kind of a spin-off on what we’re famous for, but it’s got a midrange control instead of it being fixed. And I’ve changed quite a bit of the circuit for a specific sound that I was going for, kind of that crash-and-burn ’66 thing. Nails the old Neil Young stuff, Rolling Stones. I was really going for the whole essence of the Laurel Canyon sound, of players back in the late 60s and 70s who were in that [southern California] scene.

“Right now it’s one of my most favorite amps. I think it’s just because it’s something different. It’s such a departure from that EL84 sound, and it doesn’t sound like [an EL34-based] Clubman or a Chieftain either, it’s just got its own thing.”

Onward and upward, then, with the Jamison era of a legendary boutique guitar-amp maker!

For more information about Matchless amplifiers, check out matchlessamplifiers.com.