“Heavy music wasn’t affecting me in the way it always had”: Gallows’ Wade MacNeil embraces psychedelic sounds with Dooms Children

The former Alexisonfire guitarist and Gallows singer on why punk and hardcore gave him anxiety, why he found comfort in his new “softer” side project Dooms Children, and the power of first-gen EHX pedals.

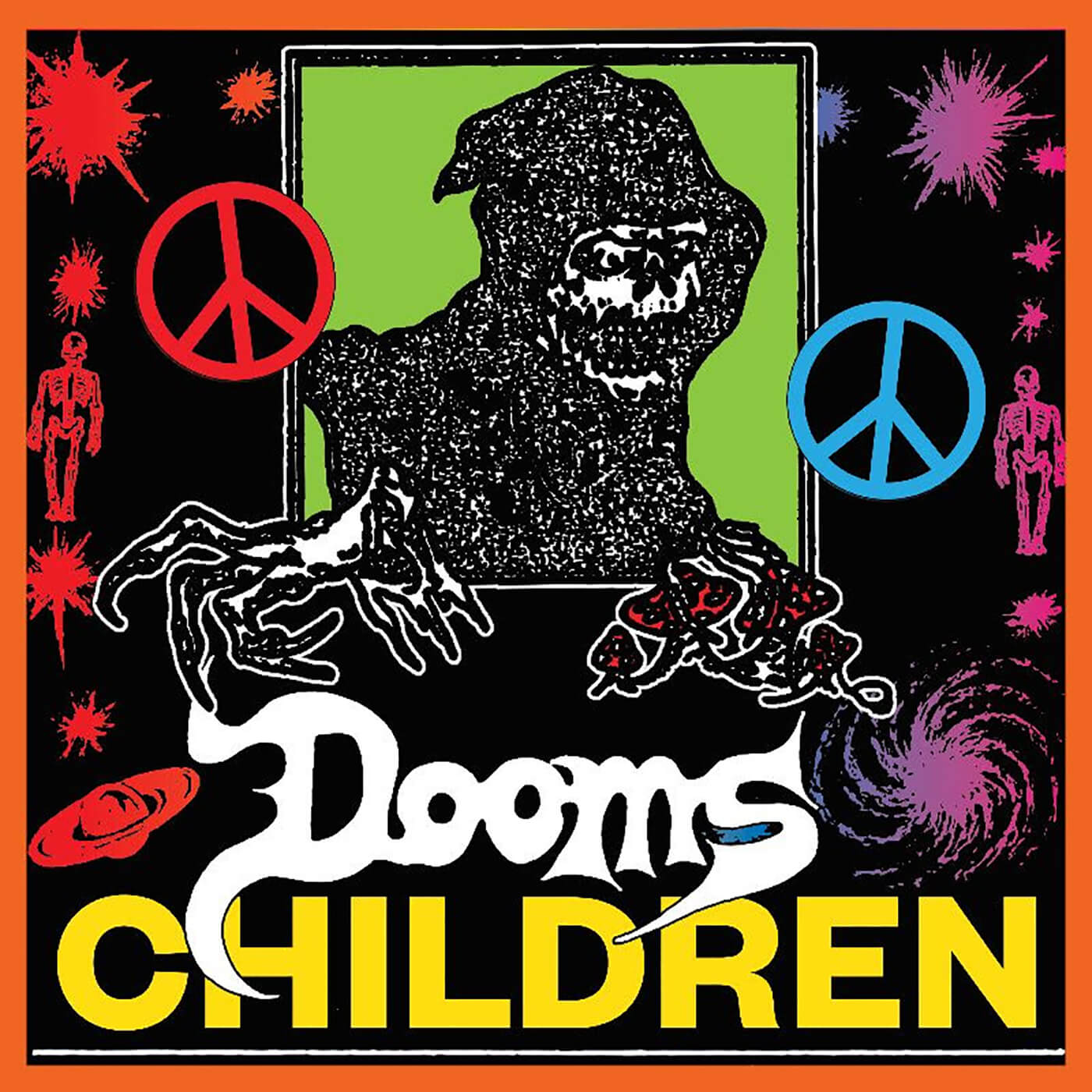

Image: Rashad Bedeir

If you know Wade MacNeil’s music, then you know that something being too heavy isn’t usually a problem. In the past two decades, as guitarist with post-hardcore luminaries Alexisonfire and vocalist with British punk rabble-rousers Gallows, being heavy is something he’s actively encouraged. But when he decided to start tracking the songs that would eventually form his new record with Dooms Children, that go-to approach loomed like an immovable object blocking his path.

In its finished state, the self-titled LP is a hazy, vibey slice of psychedelic rock informed by MacNeil’s love of the Grateful Dead and a set of collaborators, notably co-producers Daniel and Ian Romano, with a track record in delivering hazy, vibey slices of psychedelic rock. But a couple of years back, his rugged streak meant that he couldn’t find that balance during initial sessions with Canadian indie legend Joel Plaskett.

“Part of the process of doing this record was finding the Romano brothers to make it with,” MacNeil says. “Joel’s got this great studio that’s a total time warp. Everything’s recorded on tape, it’s beautiful out there. After about two days of recording – he was playing guitar on it, too – we had some very heavy sounding Neil Young tracks, and both Joel and I were like, ‘This isn’t it’. I brought a bunch of punks to play with me – a drummer who hit way too hard, and a bass player who could not chill out. It wasn’t right.”

Reference points

MacNeil has known the Romano boys since they were teenagers kicking around in the punk scenes between Welland and St Catharines, Ontario. After shelving their post-hardcore band Attack in Black, Daniel has become one of the most prolific, exciting voices in indie-rock, squaring pastoral folk with power-pop, garage-rock and Bob Dylan cover records. Here, the duo provided a sounding board, plus a deep knowledge of all sorts of nerdy engineering curios, and a shared musical language.

“It’s one thing to be in the studio with someone and have them understand your references – for me to mention a specific Shuggie Otis tune and know what I’m talking about – but Dan would know the song, how it was recorded and the instruments used in that session,” MacNeil says. “It was incredible working with those dudes. We have a lot of similar musical interests. We all grew up skateboarding and listening to Dead Kennedys records, and found our way into very different things. Dan just went through his country phase a lot earlier than I did.”

It’s perhaps not a surprise that MacNeil found the ideal team close to where it all started. Dooms Children serves two purposes: it is both a chance to flex new creative muscles and also a completely unvarnished look into a bleak, eventually restorative, period in his life. The songs were written on either side of a stint in rehab. “I found myself in this place where I felt like a lot of things were falling apart in my life about two years ago,” MacNeil says. As florid and beautiful as a lot of the music is here, his words are almost unfailingly spare and documentarian.

“When I got out of rehab, something no one knew I was doing, I thought I would put it out there,” he continues. “As I started that process, maybe it was something I was embarrassed about. I felt like a failure on some sort of level. But the more work I did on myself, it shifted the way I felt about going there. I felt good about taking steps to try and take better care of myself. It’s not a failure to work on things you struggle with.

When I was in treatment, I got an email because I’m on the Metallica mailing list. It was a letter from James Hetfield to the fans, letting them know that he wouldn’t be able to do some shows because he’d decided to go to rehab.

“I was pretty moved by that. There are a lot of people who struggle silently, and I was very happy to put it out there. I found that tons of people reached out, and it had a positive effect. I wanted to keep being straight up with people in the way I presented the songs. My music, and the way I am on stage, is the way I am. I’m not playing some fucking character. I’ve always lived the life I sing about. But this is a step beyond that. It’s difficult because it is so personal. I feel like there’s maybe more riding on it. But, on the other hand, I feel like I’ve been as open as possible and that’s all I can do. I feel like that in itself is a success.”

Heavy going

MacNeil’s decision to seek help coincided with a shift in listening habits that many folks will understand. “I moved away from heavy music,” he admits. “It wasn’t affecting me in the way it always had. Listening to punk and metal and hardcore has always been this big release of energy, and something that made me feel really good. Around that time things were so chaotic in my life that it felt like it was giving me extra anxiety.

“I moved into a zone of listening to a lot more 60s folk and older rock songs, things that were a little softer in terms of my own trying to feel better. My interest in making a record like that was growing, and I kind of wrote about half the songs through this very chaotic zone of my life and then wrote the other half after getting clean and putting the pieces of my life back together. When it got time to do the vocals, I recorded them sequentially from when things were the worst to coming through the fog. For me there’s really a lot there. I tried not to hide any of it. I tried to be very direct.”

The idea of release is very important to this story, and it’s something that people reared on punk and hardcore generally need from music. In that space catharsis, and healing, are often facilitated by screaming your guts out. But MacNeil has also found it in these winding, open-ended Dooms Children songs, with a little help from the Dead.

“It’s around this time that I really, really became a huge fan of theirs,” he says. “I was finding a completely different kind of release. Their ethos is very fucking punk. All the creative decisions, and everything the band did, laid the foundations for counterculture. There are no rules. That’s always exciting as a musician. More than that, though, there’s this kindness in the music that is really special to that band. Even in the songs that are the saddest. That’s something I really identified with at that time. I don’t think I’ve really found it in any other band. I wanted to get a bit of that energy into this record.”

Vintage charms

Transposing this feeling from his head, through the composition of the songs, and into recorded form involved a stack of vintage gear, and an approach that foregrounded honesty to complement the lyric sheet. The record was tracked largely live, with one-take solos and songs captured on the second or third pass, max. Alongside MacNeil’s go-to Les Paul Junior and a handful of Gibsons and Fenders from the 50s and 60s were pedals and amps that delivered era-specific authenticity.

“There are a lot of first generation Electro-Harmonix phasers, reverbs and delays, an old Big Muff, a first gen RAT,” MacNeil says. “Probably 80 per cent of the guitars were recorded through the same 50s Fender Princeton. To slightly change it up, we used a really old Fender Champ – just ancient combo amps the size of a large book.”

These songs can get pretty hairy at times – witness the outrageous wigout at the heart of Lotus Eater, which goes full space-rock after sneaking in a lyrical reference to the Misfits classic Where Eagles Dare – and MacNeil is stoked on the idea of drawing things out live, finding fresh pockets of space in which to improvise. A lot of that searching energy seems to emanate from the opening strokes of Morningstar, a huge highlight that combines patient acoustic chords with a dense groove and nimble leads. It was the first song up to bat when they hit the studio – both with Plaskett and the Romanos.

“It was about allowing there to be a much wider scope of playing on the record,” MacNeil observes. “Morningstar was the proof that it was going to work. A great thing happens on that song that happens on a bunch of songs, which is a guitar solo, followed by a different guitar solo, followed by two guitars soloing at the same time. That’s a bit of a Dooms Children move. It’s my favourite thing that happens on the record. There’s a very clean, phased-out solo. I think that’s very expressive in a different kind of way. This project has allowed me to do that, and it’s a real representation of where I am musically and where my head’s at.”

Since wrapping the Dooms Children debut, MacNeil has worked on things that stick closer to his established blueprints. He doesn’t expect the fingerprints this style of music has left on him to fade, though. “Everything builds on the last record you made,” he says. “Since recording this I’ve made a bunch of heavy records. It certainly bled into those. I’ve become a wah-wah guy.”

Dooms Children is out now through Dine Alone Records.