“I’ve never really understood what purpose I have in the guitar world” Ben Howard on the wandering spirit at the heart of his new album

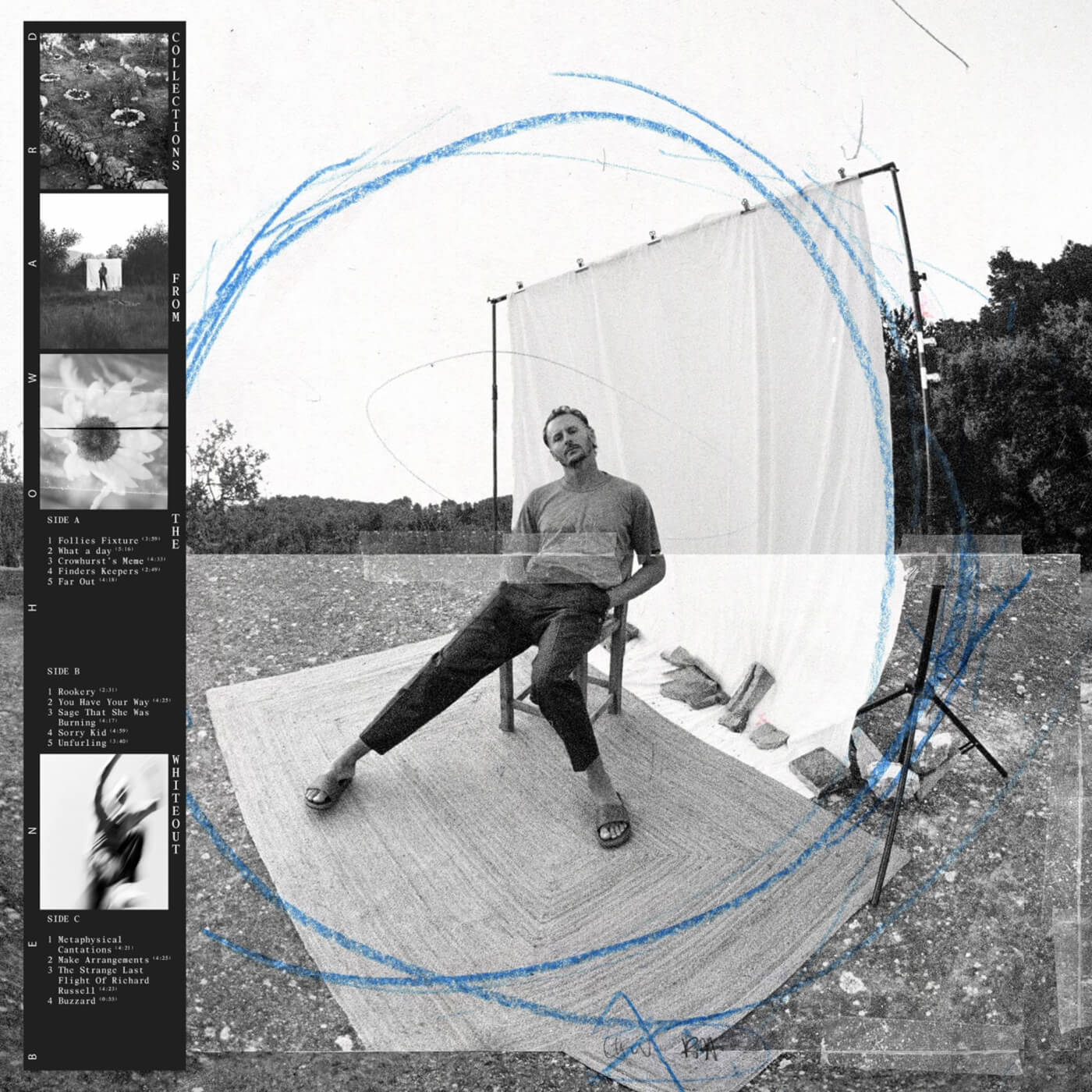

The English singer-guitarist on staying in his own head, keeping things interesting for everyone, and working with Aaron Dessner on new album, Collections From The Whiteout.

Image: Venla Shalin / Redferns

Collaboration is the heart and soul of most great records, whether that’s a band toiling in a cheap rehearsal room, files appearing in Dropbox folders, or a singer-songwriter batting ideas back and forth with a producer. Ben Howard has always chosen his creative allies carefully – they’re people he knows and trusts, with the bulk of the weight usually resting on his shoulders. But things are different now. On Collections From The Whiteout, his fourth album, the other key voice in the room is a new one. It belongs to Aaron Dessner of The National.

On paper, this pairing reads more like a bout for the title than a tag-team outing, with the English folk-derived peculiarities of Howard’s guitar playing and phrasing up against someone who has helped to make textural innovation and widescreen melancholia a serious currency in American music. But as Howard tells it, it was in fact a low-key, complementary match up. “We just had a good time making it. No fuss. No big story behind it,” Howard says while encased in a Zoom window, a rollie between his fingers.

“Our musical heritages are quite different but we found a familiar space in among it all, like the way we approach instruments, or the way we approach pedals and sounds. Jon Low, the engineer, threaded that discourse and pulled us in from different areas we were orbiting. We’re both ideas people. I wouldn’t say I’m that proficient on any instrument, but I like to chase a thread. I’m pretty relentless. I need someone to pull me in at points.”

Collage admission

Collections From The Whiteout, which follows 2018’s sprawling indie-psych exploration Noonday Dream, is brimming with ideas. It amps up almost every element of Howard’s palette, delighting in complex layering and transposing the delicate nature of his melodies into a world of complex, unknowable sonics. Take the collage-like Make Arrangements as a particularly good example: there’s no riff to speak of, and little in the way of pronounced shifts in pacing or tone, but there are solid, meaningful hooks floating amid its shards of sound.

“My attraction to Aaron in the first place was because that is what he’s doing at the moment – working on a lot of layered harmonies,” Howard says. “Make Arrangements is a harmonised bass part that was very freeform, with beats and very few musical elements to it. But it’s about realising that it’s engaging enough to be a song. We started realising that is a theme, that relentless nature of a song.”

There is a healthy side of form mirroring meaning at work here, too. This is an album of its time, reflecting the preoccupations of its writer and also the environment in which its first seeds were planted. Howard has rolled his eyeballs over thousands of headlines in recent years, filing dispatches from a bitter, divided world governed by fools alongside curios and stories that define strange but true: sailors who turned to subterfuge in the face of failure, fraudsters at home in any crowd, tragic flights ending on deserted land in the Puget Sound.

Collections From The Whiteout is almost an attempt to declutter his brain. He winds these tales around aspects of his life and binds them to the record’s searching, loop-heavy compositions. “It’s impossible to truly get away from everything these days,” Howard says. “But that’s my remit. That’s my payroll. That’s my job, so to speak – to tinker around and stay in my own head.

“I think this record was perhaps an acceptance of that. It certainly was a lot of useless information I seemed to have obtained, and I wanted to somehow sift through it into a cohesive set of songs. I realised that there’s a deep crossover between every tiny little detail in everyone else’s stories with my own experiences, and that you can thread a fairly cluttered path through it and come out at the end of it with a few songs.”

Funny guy

But the clutter is essentially the point of the exercise. Howard is liable to get lost in a song, poring over each movement, driven by a desire to make unusual choices and follow each idea through to some sort of a conclusion. Lyrically, the album also taps into that. It is an episodic, surrealistic exercise, like hiding an inappropriate guffaw behind clenched teeth. The album is at its best when these twin concerns clatter into melodies that offer a playful sense of pattern and circularity, knowingly doubling down on the narratives and jokes in a sea of delay and helter-skelter atmospherics.

“With a song you’ve got so much you can play with,” Howard says. “It’s not just the lyrical content. It’s not just instrumentation. It’s form. It’s little references and reference points. That’s what makes it interesting. It’s a free for all when you come to put these things down. I enjoy being able to have fun with that. I enjoy the duality, and it not being a concrete thing.”

“The absurdity element was certainly something I wanted to include. I’m a big Roald Dahl fan, and a big fan of old English literature,” he continues. “To be honest, I was really disappointed that the record wasn’t funnier. I’m always trying to be funny, and I think that’s where the duality comes in – the crossover of story and self. I listen to a lot of artists who are a bit more tongue-in-cheek. I think inevitably you’re almost trying to copy aspects of people, or get across a sense of humour.”

Howard started out a long way from this self-reflexive spot. As a kid he moved from Middlesex to Totnes, Devon, and his emergence in 2011 with the smash hit LP Every Kingdom very much played upon the surfer dude persona that has lit thousands of gap year beach bonfires. Pairing the long-simmering influence of John Martyn with melodic smarts and a knack for low-key pop framing, it capped off one of those years-long overnight success stories we’re always hearing about. Having racked up hundreds of shows across Europe under his own steam the vibe quickly shifted – in place of club nights in Belgium witness multi-night stands at Brixton Academy, arena dates in the US opening for Mumford and Sons, and headline-grabbing Glastonbury sets.

Shortly after winning a brace of Brit awards – for British Breakthrough Act and British Male Solo Artist – Howard put out his second album I Forget Where We Were. Released in the autumn of 2014, it was a sharp left turn into wiry acoustic leads and restless songs that bled into one another across a mammoth runtime of almost an hour. It was difficult, anxious and alienating. It was not the easy option.

It treated his audience like engaged listeners and grown-ups, and began a process of reframing his live show as an ongoing, often introspective, interrogation of his music. “It’s got to be interesting for everyone. In a selfish way it’s got to be interesting for the artist as well,” he says. “There have often been people disappointed at the catalogue we play live, and for me we have to strike that balance together rather than it being a one-way conversation.”

At this remove it’s fairly straightforward to see that Collections From The Whiteout doesn’t get written by the man who decides to cash in on Every Kingdom’s recipe for success. “It was an important decision,” Howard says today. “I got a hard time for it across the board. If anything, it made me more resolute in [believing] that there were more interesting things to do. I couldn’t see me doing it any other way, so it was a bit of nonsense. I didn’t understand what all the fuss was about. I don’t think I’ve ever expected that [repeating yourself] off artists I like.”

No defaults

Seven years along the line, Howard is still difficult to pin down. When asked about his approach to recording guitars, he’s reluctant to attach his colours to any one instrument, piece of equipment, or mode of working. “I have no tried and tested,” he admits. “I have no default setting. I make it quite difficult for myself and I definitely make it difficult for other people. It was more coming in with a load of strange ideas and seeing whether any of them were workable.

“I’m always fucking with the guitar, really, and trying to get something else out of it. There’s guitar through Moog. There’s always a lot of delay. I play guitar quite rhythmically, and I find it’s often more important than melody. There’s a weird fusion of the two when they’re in the right proportion. But, then again, I came in with a couple of top lines as well. My setup was all over the place.”

From the outside, Collections from the Whiteout suggests an approach that leans towards reshaping its guitars as elements within a wider firmament, manipulating them so as to remove the idea of a dominant force. But the opposite is true. Travelling to Dessner’s backyard in New York – pre-COVID, and pre-Dessner decamping to the forest to make Folklore and Evermore with Taylor Swift – threw up practical issues that they factored into their work. Howard travelled light, with only a 1920s Martin parlour guitar for company.

“We were constantly trying to make guitars sound like guitars,” Howard observes. “The picking is the backbone of it, but I’m always getting told off for trying to make weird noises. This process was trying to align it with something that was a bit more literate. It was nice to go back to the acoustics a lot more, and that was really an element of what guitars I could take because the customs are so strict. They always give you such a hard time, it’s such a welcome committee to America. You get the third degree. All of that shit feeds into making a record.”

On Collections From The Whiteout, the electric guitars also cover a lot of ground. Its shifting priorities mean immediately following the Mark Knopfler-esque leads of What A Day with the distorted skronk of the TV on the Radio-style Crowhurst’s Meme. Howard’s work, live and in the studio, is largely completed through the medium of Fender Jazzmaster. “It’s a ‘65, left-handed,” he says. “I’ve been looking for a left-handed Silvertone or something, but I end up finding a right-handed one and figuring out how to play that. I end up playing a lot of right-handed guitars upside down. I don’t think it’s very good for my playing, but it meant that I deep dived even more into delay world. Now, I’ve tidied it up and organised my life a bit, and I’m trying to fingerpick more.”

“I’ve never really understood what my guitar playing is and what purpose I have in the guitar world,” Howard admits, and this off-balance view of his work is stapled to Collections from the Whiteout. As time stretches away from Every Kingdom he appears to be both retreating into himself and broadening his horizons, as though the musical answers he’s after will be found both within and without.

“I don’t really approach writing in a set way,” he says. “This was an opportunity to experiment with words and music together and see where those little fusion points work and where they don’t. It’s the same with harmony. There are a lot of harmonies on this record that shouldn’t really work, but they did. It was work across the board in terms of vocals, musical arrangements, lyrics, fragments of poetry, obscure references, and I always struggle with the fact that I’m not succinct enough.

“I read something about Leonard Cohen years ago, that he was always trying to simplify things because he realised that made for a better song. I’ve always gone the other way because perhaps the weirder the better, I find. We’re obsessed with meaning these days. I’ve done a couple of interviews where, straight out of the gate, everything is ‘What does this mean, what does that mean?’ I find the question marks are the interesting part of it.”

Collections From The Whiteout is out now on Island Records. Ben Howard plays a one-off global live stream from Goonhilly Earth Station, Cornwall, on 8 April.