Related Tags

The Unwritten Future Of Guitar: Off with their heads – the future of headless guitars

Boutique Guitar Showcase boss Jamie Gale considered the past, present and future of headless guitars.

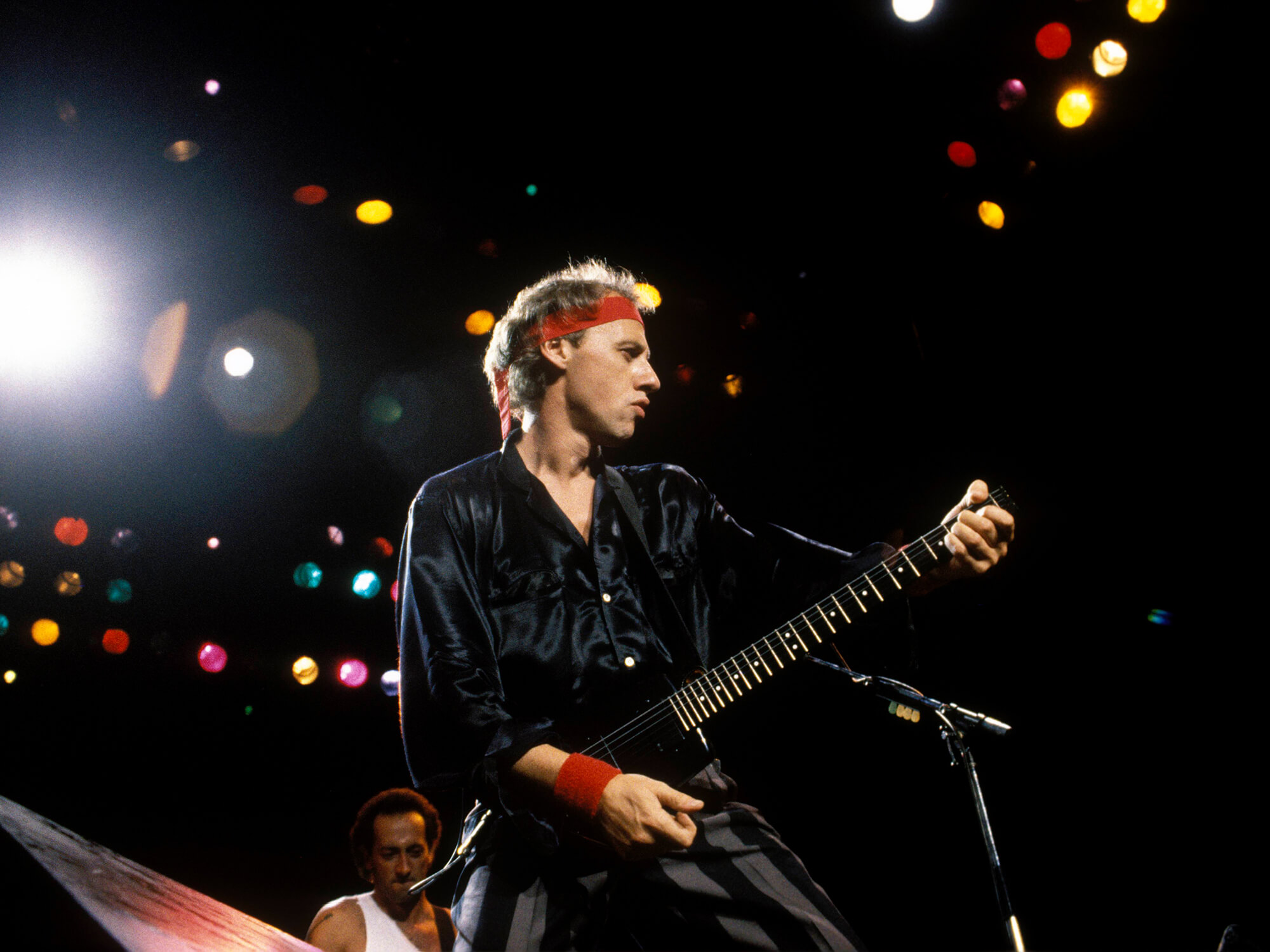

Mark Knopfler performing live onstage, playing Steinberger guitar. Image: Bob King / Redferns

In his new column charting the bleeding edge of modern (and future) guitar design, Boutique Guitar Showcase boss Jamie Gale delves into American folklore and a few legends of luthiery.

I have been travelling the world with unique, world-class instruments for decades, having conversations about the objects that form our shared obsession and what it is we love about them (and what it is we don’t).

- READ MORE: Cause & Effects: Tube Screamer season has arrived – but why do guitarists love this pedal so much?

In recent years, I’ve had customers come to events and walk right up to me to proclaim, “I play headless guitars”. That’s a strange thing to do… what a curious thing to say… they’re not only not interested in any guitar with a peghead, headless guitars are part of their identity.

It got me thinking about headless guitars. First of all, the name ‘headless’; it’s such an odd way to describe something. It evokes images of American folklore – horseback ghosts seen from a distance, threatening to hurl flaming pumpkins at you. But I suspect the origins of the headless guitar have less to do with ghost stories and more to do with practicalities. Let’s see if we can find the source.

The guitar’s traditional form, with its headstock or peghead, I suppose, was a matter of function; the string tension or pitch must be adjusted in order to tune the instrument. The luthier’s solution involved a tapered peg with a hole in it, through which the guitar string was fed. The tapered peg was then pushed into a hole, where its design would allow it to be rotated under tension in order to facilitate the tuning of the string. The hole in which it was placed was simply a void in a solid piece of wood, strong enough to withhold the demands of the peg under tension. This wood that received the peg was named the peghead.

The geared tuning machine eventually replaced tapered pegs, yet the peghead remained a good place to mount the new geared metal tuners. Since these were acoustic instruments, the thin wood of the body didn’t have the structural integrity to support these new mechanical improvements. Though the peg was now obsolete, the name peghead remained.

Fast-forward to the invention of the solidbody guitar in the early 20th century. These new solidbodies allowed for the possibility of mounting hardware somewhere other than the peghead – and yet it remained there for decades more, seemingly unconsidered. Until the late 1970s, that is, when designers such as Ned Steinberger reconsidered the electric bass guitar, deeming the peghead unnecessary and moving the tuning machines from the nut end of the strings to the bridge end, a radical move at the time.

How did this come to be? According to Steinberger, he was struggling with the balance of the electric bass. The long neck topped with large metal machineheads was causing neck dive. It was like two children of approximate age and size on a playground seesaw – they’re never really equal. One is always a little heavier than the other, which is all good fun when you want the up-and-down motion but requires great effort to keep stationary. It’s a common (and tiring) problem for bass players, having to support their guitar’s neck with their fretting hand while playing.

Why wasn’t the bass designed with proper balance? Shouldn’t it stay in playing position? The body shape with strap pins were modern designs yet the instrument wasn’t designed to stay in position without additional support?

My personal suspicion is that the bass guitar was not as well considered as the preceding electric guitar. It was simply a larger-scale version of its similar-looking, higher-voiced sibling, which is common in design extensions. The first is well considered, the rest not so much. Many of the most iconic guitars in history have balance issues, even if many of them have silhouettes like their more thoughtfully designed predecessors.

Can’t think of any examples? Let me help you.

Let’s say there’s a guitar maker famous for producing hollowbody archtop guitars, who now wants to offer a solidbody that looks like their already famous instruments. The plan? Re-use the archtop silhouette and transfer most of its design language – carved top, pickguard, etc. Maybe there’s a maker with a successful electric guitar model who wants to offer an on-brand bass – they’d simply make it bigger and longer, right? This stuff happens all the time.

And so we have a balance problem. In the late 1970s, Ned Steinberger decides he can solve it. I mean, there are only ever three possibilities, right? Shift the centre of balance, add weight to the light side, or reduce the weight on the heavy side. Ned’s solution? Like a nefarious monarch: off with its head!

Did it work? Indeed it did. The scales were righted, and the bass suddenly hung in playing position unsupported by the fretting hand. It wasn’t long before this design was extended to the bass’s little brother too, and the first headless guitars arrived on the market.

At this point, the conversation about balance became one of ergonomics. Balance is but one part of the ideal human interaction with an object (but we’ll save that rabbit trail for another column). We’re going to stick with the peghead for now.

The tapered peg was eliminated once there was a better way to achieve and maintain string tension. This was a functional improvement that made the experience of playing guitar easier and more enjoyable. And the invention of solidbody electric guitars meant that there were other viable options for mounting the tuning machines.

But is that all there is to the peghead? Not according to Ken Parker. Like Steinberger, Parker made his name reconsidering the electric guitar with the Parker Fly. Parker, however, didn’t eliminate the headstock from his designs, citing the “after-string” as a crucial part of the guitar’s performance.

What’s after-string? It’s the string that exists beyond the nut and saddle. It’s not often played but this additional string length does affect string tension and, to a lesser extent, harmonics (which can be a problem for guitars with a trapeze tailpiece). Parker believes that musicians won’t be willing to adapt to the feel of a guitar without the after-string, recalling customers’ negative reactions in the early days of floating tremolos, back when he was still running a repair shop.

In a recent conversation, Parker recalled a customer’s distress when he played his beloved guitar after installing a floating tremolo. Why did it feel so different? ‘What have I done?!’ This is when they found that simply releasing the locking nut (re-activating the after-string) would be enough to make the customer happy with their new modification. From here, Parker decided that a reduced-mass peghead, which keeps the after-string in play, was perfect for the Parker Fly. His peghead, which he still employs on his current archtop guitars, has become iconic. Any other maker using such a minimal peghead will live with the Parker reference for years to come.

Innovations are rarely accepted by the existing market. People become too accustomed to their playing habits to accept true change. Rather, it takes those willing to explore new possibilities to gain traction for the non-traditional; those willing to exchange one set of perceptions for another, stimulated by the new experiences they offer. These experiences lead to new music, and when enough good new music has been made using the evolved instrument, people get inspired by that too. Don’t believe me? Just look back to the instruments you love, and think about who made them famous. I suspect you’ll find that they weren’t playing the music of their parents.

These musical explorers are not bothered by the change in feel of a guitar. They’re inspired by how it changes their approach.

More than four decades after Ned Steinberger made the headless guitar famous, a growing number of players and makers are embracing its design.

What does this mean for the future? Will the peghead tuning machine eventually disappear, like the tapered peg did? Will the guitar have its head permanently removed and be condemned to American folklore for the rest of time? Who can say? The future can be hard to see – especially if you’ve lost your head.

For more features, click here.