Five Neil Young songs that guitarists need to hear

Heard people talk about Neil Young but never known where to start with someone with such a large and iconic back catalogue? Start Me Up is here to give you a five-track primer for guitar players…

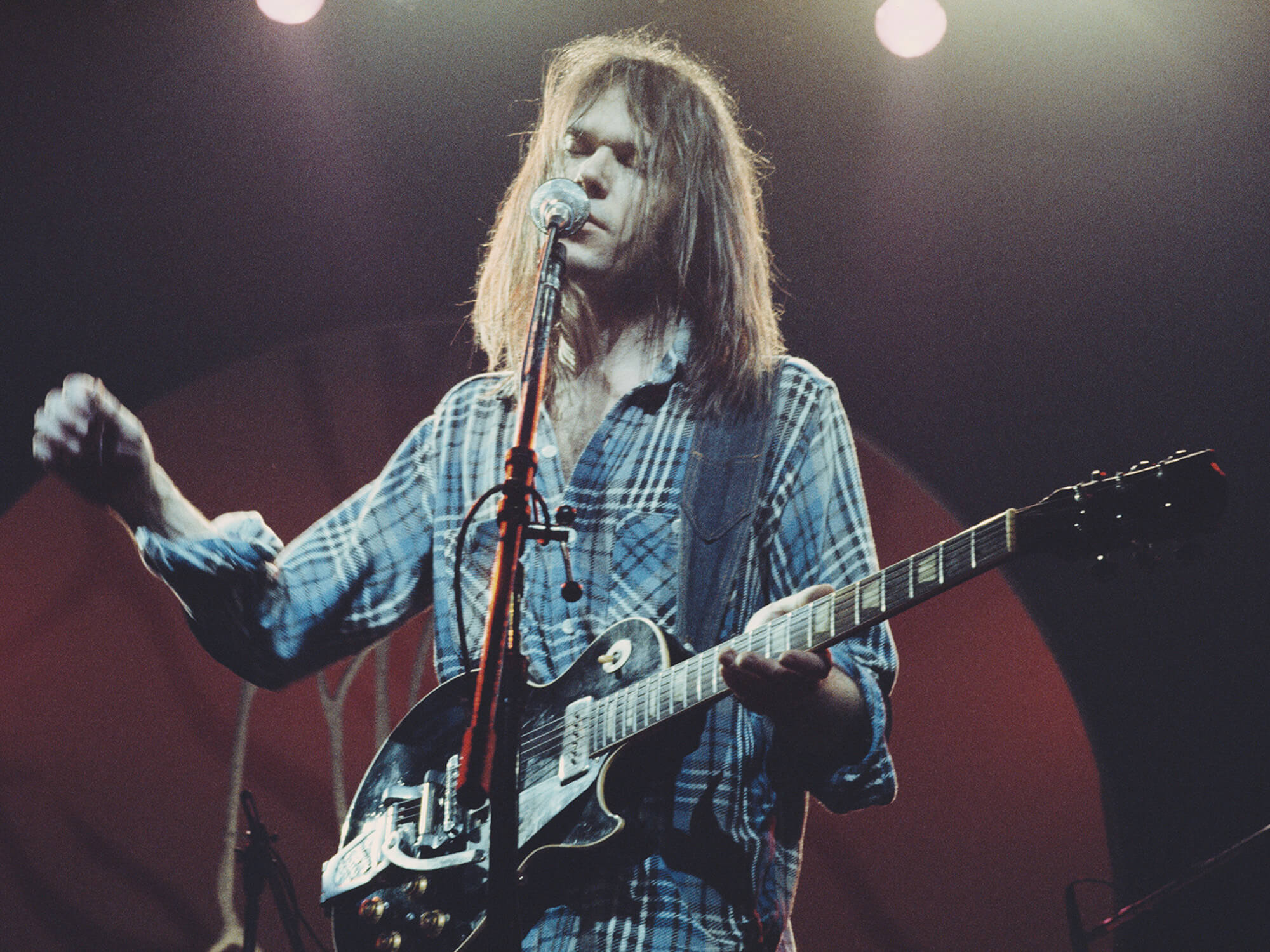

Neil Young performing in London in 1976. Image: Michael Putland/Getty Images

For most of us, Neil Young has always been around. Since arriving with Buffalo Springfield in the mid-1960s, he hasn’t slowed down, releasing more than a half-century of records in assorted configurations across seven decades. Through trends and styles and addiction and slumps and experiments, he has been around.

The steady, almost routine, arrival of a new record every couple of years was once likened to “a baseball slugger swinging his way in and out of slumps” by critic Steven Hyden, but Young’s music itself has never been steady or routine. Whether he was angry, sad, in love or out of it, releasing good music or bad, his guitar was a divining rod for emotion.

Young’s main squeeze since the late 60s has been a 1953 Gibson Les Paul Goldtop (which was daubed with paint to give it its iconic name ‘Old Black’ before his time with it) that features a Bigsby, a P-90 at the neck and a Firebird pickup at the bridge, into a 1959 Tweed Deluxe. His electric playing surges and squalls, peeling off from irascible riffs into elongated, rugged live jams, while his acoustic work (often in the company of Martins, including a famed 1941 D-28 once owned by Hank Williams) lopes and struts from Laurel Canyon contentment to the deepest, most hopeless recesses of his mind.

Following a couple of go-rounds with a rejuvenated Crazy Horse, his new record Before and After comes from a reflective space – a familiar one given his late-career archival releases and penchant for revisiting pockets in his own history – and reveals a musician who won’t settle. Here, we take a look at five songs from Young’s career in order to provide a way in – consensus picks aren’t really a thing in his world, so view them as an invitation to dig deeper. If he can still find fresh avenues to travel along as an artist as he approaches 80, so can we as listeners.

Start Here: Down By The River (Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, 1969)

In many of Young’s most arresting guitar epics, there is a feeling of something ending. Not just ending, but ending badly. An impending doom sort of thing. Down By The River is ostensibly a murder ballad about some loser with a temper who can’t take rejection, but it’s tied up in a nine minute descent into the void that seems to signal the end of hippiedom, maybe, or the end of everything.

Young’s soloing is a needling, passive aggressive marvel, with Danny Whitten firing back barbed notes of his own at every turn. In acoustic arrangements – such as the one on Live at Massey Hall – Young’s isolated voice hews more closely to the yowling violence of the song. In tandem with Whitten, the harmonies of the original offer a complex, syrupy cocktail of darkness and light.

Then Go Here: Tell Me Why (After the Gold Rush, 1970)

Following his secondment into Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young for the folk-rock blockbuster Déjà Vu, Young stayed in that lane, jagging away from the noisier confines of Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere into a pastoral, country-flecked mode that would define half his career, with 1972’s Harvest going supernova and setting up a years-long artistic reckoning.

After the Gold Rush’s title track and Only Love Can Break Your Heart are all-timers, but Tell Me Why is the perfect stall-setter. It transposes the brittle grandiosity of Young’s melodies from the rowdier confines of early Crazy Horse into something altogether more ruminative and emotionally prescient, with Young and Nils Lofgren’s guitars engaged in gentle jousting, finding new pockets of space and quickly occupying any left behind by the other.

Stop Off Here: Like a Hurricane (American Stars ’n Bars, 1977)

The first 10 seconds of this stone-cold classic tell you an awful lot about how Young goes about his business. The picked, descending octave riff is almost molten, flowing out at skull-rattling volume. But it’s also plaintive and undeniably beautiful. It’s also the tether for a solo where Young really cooks, keeping him earthbound when he threatens to get all cosmic on us. Given its combo of power, melody and ready-made space to get out there, it’s not a surprise that this has become a mainstay of Young’s set, alongside similarly rockin’ bankers such as Powderfinger and Cinnamon Girl.

On Weld, his grunge-era masterpiece of a live record with the Crazy Horse line up of Frank ‘Poncho’ Sampedro, Billy Talbot, and Ralph Molina, the swampy, bad-tempered Iraq War-era vibes in the room reshape its energy into something altogether more gnarly. There, it becomes a straight-up brute, stretching out to 14 minutes before collapsing into sense-shifting shots of noise.

Almost Home: Sedan Delivery (Rust Never Sleeps, 1979)

The live/studio hybrid Rust Never Sleeps has a couple of truly monumental bookends in the acoustic My My, Hey Hey (Out of the Blue) and electric Hey Hey, My My (Into the Black), but it’s worth making time for its rowdiest, most unruly moment. Inspired by Devo and running on stomping, snotty punk energy, this staging of Sedan Delivery is an eye-bulging garage-rock rager, where Talbot and Molina lock into a pummelling groove and just keep rolling until the hook falls out of Young’s mouth.

Beginning life as a Zuma offcut and released elsewhere (on Chrome Dreams and Way Down in the Rust Bucket, for example) as a more even-tempered country-rocker, this take shows Young’s desire to follow energy and the moment. At a time when punk was reframing what rock meant, he wrestled with his own sound and found an outlet in something he was coming to understand in real time.

Nightcap: Tired Eyes (Tonight’s the Night, 1975)

There are profound bummers, and there’s Tonight’s the Night. Ground down by the realities of commercial and critical success, reeling from the deaths of Whitten and his close friend and regular roadie Bruce Berry, Young served up an album length howl that culminated in Tired Eyes, a seething, lonely masterpiece of bad decisions and worse consequences.

With Ben Keith pulling gorgeous, liquid misery from his pedal steel and Young strumming as though the guitar might fall from his grasp at any moment, the song builds, builds, builds and fades away time and again around the repeated, pleading, futile refrain, ‘Please take my advice…’.

Where next?

Young has always been a shapeshifter, so you could get lost along any path and find something worthwhile. His later work is spotty but often really good – from the hulking Walk Like a Giant to the blown-out pandemic era Crazy Horse set Barn – while his desire to interrogate his own back catalogue through his Archive project has led it to become a living, breathing thing. It is malleable given shifting contexts and always ready for reappraisal, preventing it from becoming another stale, untouchable classic rock monolith.