Leo Fender: The guitar genius who couldn’t play a note

On what would have been his 110th birthday, we look back at the life and times of Clarence Leonidas “Leo” Fender – the man whose maverick approach to guitar and amplifier design changed music forever.

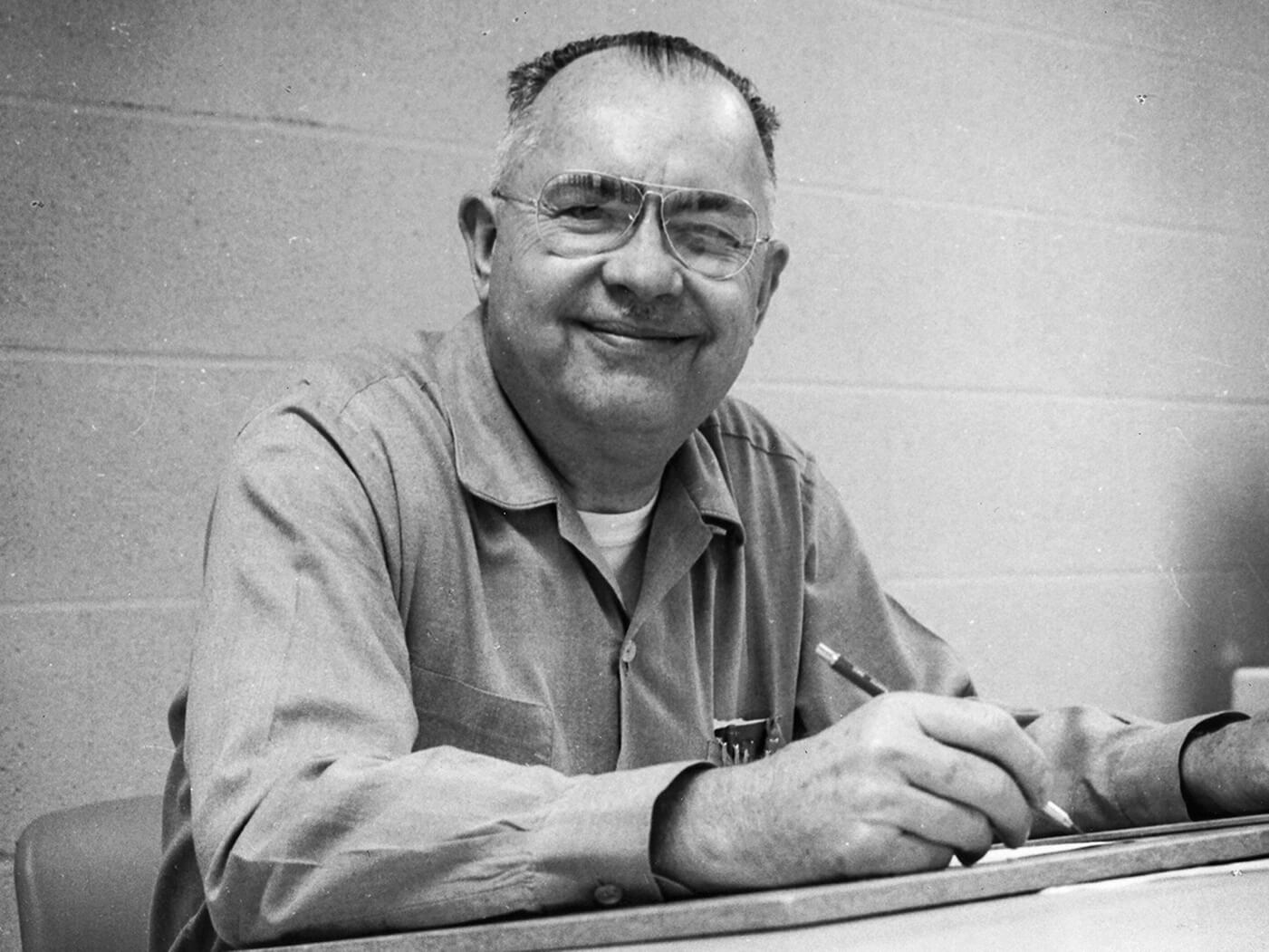

Leo Fender at the drawing board. Image: Bob Perine

If Leo Fender had somehow managed to survive until his 110th birthday, he wouldn’t have wanted much fuss. Rather than consider how to blow out 110 candles on that big cake, he’d much rather have ambled to his workshop, where he could work alone more satisfyingly on the new pickup he’d been toying with for the last few months.

But he never made it that far. The day before his death in 1991 at the age of 81, the single-minded Leo had been at his work bench at G&L, the company he started in 1979 with his longstanding colleague George Fullerton.

“Leo certainly was a hardworking person,” George told me, “and he was not pretentious. He was not the kind of person who wanted to be a big shot, if you want to call it that, and never was. Even up to the day he passed on, he was Leo. He was a difficult man in a lot of ways, a really strong-minded person. The ideas he had, you didn’t change him. If he had an idea to try something, the only way you’d ever change him would be to prove that what he had would not work.”

Before G&L, there was Music Man, set up in 1970 by Forrest White and Tom Walker. Leo officially joined them a few years later, adding basses and guitars to the existing amps. Music Man was acquired by Ernie Ball in 1984, by which time Leo had already gone off to set up G&L. And, of course, before all that there was Fender.

Leo’s legacy is right there in his surname. That Fender brand name and that famous Fender logo survive to this day, and who knows, they might still be here 110 years from now. But it could have been Finter. Six generations before Leo, his four-times-great-grandfather, Hans Finter, arrived in the United States. Hans emigrated from Germany, naturally unaware of the importance his surname would acquire when the Finters changed their name to Fender.

The opening bars

By the time Leo was born in 1909, the Fenders were based in Orange County in Los Angeles. Young Leo started work there as an accountant, but his hobby was electronics. He took a few piano lessons before trying saxophone but wasn’t serious, and he never played guitar. He lost his accounting job during the Depression, and in 1938, 29-year-old Leo opened his first radio repair store, in Fullerton.

Leo busied himself assembling a few PA systems that he hired out to sports gatherings and dances, and he met local musicians at the new store, among them a professional violinist and steel guitarist, Clayton Orr Kauffman, known more simply as Doc. Leo and Doc set up as K&F and made electric steels and small amps in the back of the radio store. Don Randall at the Radio & Television Equipment Co got to know Leo, and Radio-Tel became the exclusive distributor for K&F. Doc pulled out early in 1946, and the firm struggled. Leo revised the setup and called his new company Fender Manufacturing, renaming it the Fender Electric Instrument Co at the end of 1947.

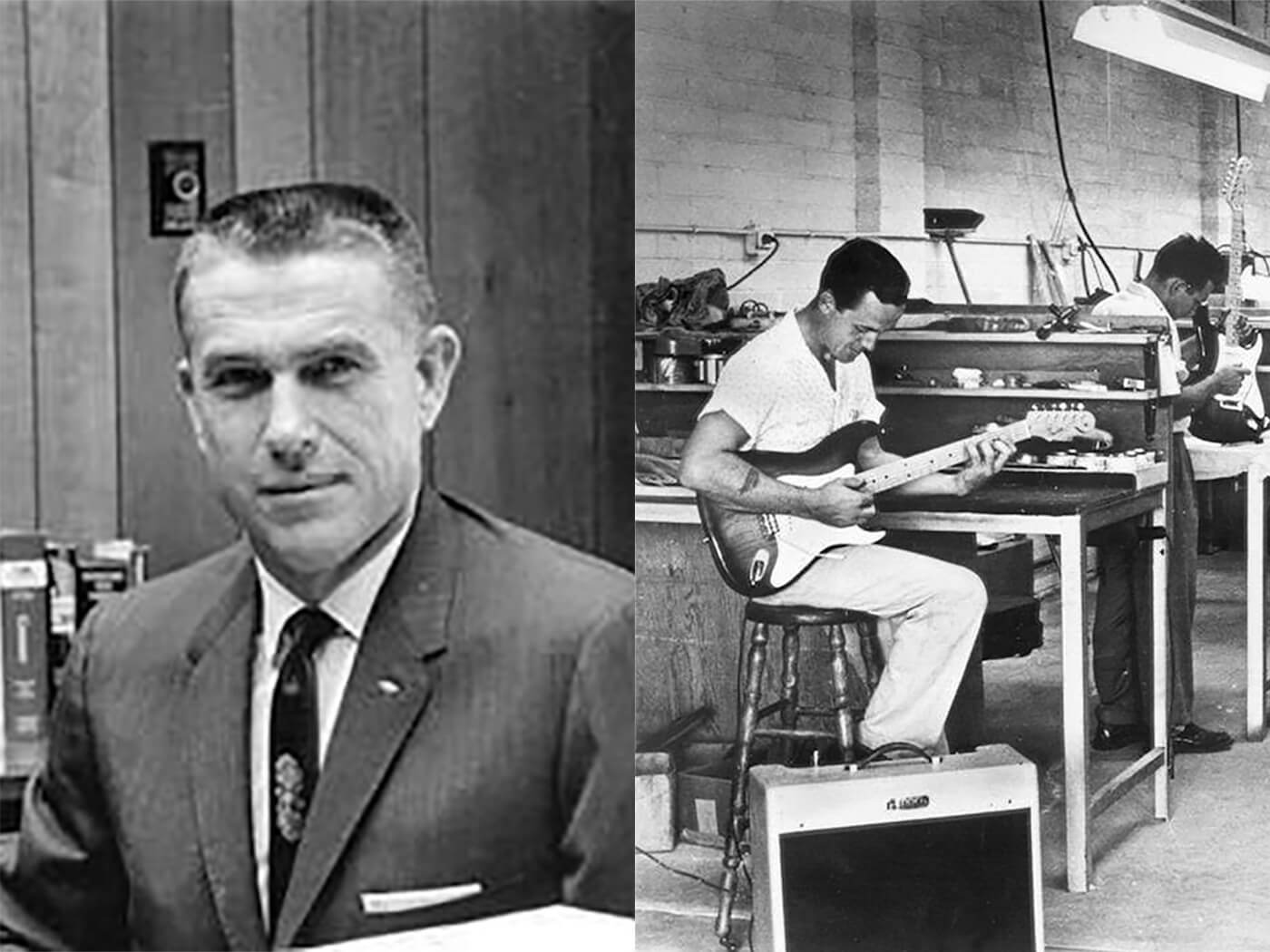

Dale Hyatt joined the team and later became an important Fender salesman. George Fullerton, an amateur guitarist, came on board early in ’48 and gradually moved from repairing radios to fixing amps and steels. Business was still slow, but Leo and his few employees made Fender steels and amps and gradually developed new models. He expanded into new premises in Fullerton, separate from the store which he sold in ’49.

Leo was an introverted, hard-working man who enjoyed long hours and selfless application to the job, happiest by himself mapping out designs for new projects. He thought that if there was a product on the market already, he could make it better and cheaper, and make a profit in the process. “Leo was a strange man in a way,” Don Randall told me later. “He had a fetish for machinery. Nothing was done economically, necessarily. If you could do it on a big machine, well, let’s buy the big machine and use it, when you might have been able to buy the part the machine made a lot cheaper from a supplier.”

Spanish translation

Leo began to think about designing an electric Spanish guitar. There were only so many customers for the steels, and there seemed to be a taste developing for something new. Toward the end of 1950, Fender started production of a radical new solidbody guitar, the Fender Broadcaster. Gretsch complained about prior use of the name, and by April of the following year the new Telecaster name was on headstocks.

The Telecaster fulfilled Leo’s aim to design an electric Spanish solidbody guitar that would be easy to build. He wanted a relatively simple and unadorned guitar that served a practical purpose: it did exactly what the player wanted as soon as he plugged it into an amp. Leo used what he saw before him, adopting some of the features he’d tried with his steels, including a bridge and integrated slanting pickup. The Telecaster was a startling innovation, the world’s first commercially successful solidbody electric Spanish guitar.

Later in 1951, Fender followed with another cracker, the revolutionary Fender Precision Bass. Two years later, the steel guitarist Freddie Tavares joined the Fender team and soon began helping with the design of a new Fender solidbody, which became the Stratocaster. Leo and Freddie listened hard to guitarists’ comments about the “plain vanilla” Tele, a task that often took them out to the local music clubs. Leo reckoned about 25 percent of his working day was spent talking with musicians to find out how he could make Fender products best suit their needs.

Forrest White joined the team in 1954, working with Leo to sort out the systems at the new factory buildings on South Raymond in Fullerton. Leo seems to have viewed the Telecaster and the Stratocaster not as individual instruments but as a single design in progress, a sort of developmental whole. He really thought the new improved Strat, introduced in ’54, would replace the Tele.

What happened, of course, was that Fender created an outstanding quartet of original solidbody guitars, the Telecaster, Precision Bass, Stratocaster, and Jazz Bass. Along with an impressive line of amplifiers, they would provide the basis for Fender’s commercialisation of the new solidbody electric guitar and the company’s rapid rise as a powerhouse behind the 60s beat boom.

Big money

Meanwhile, the huge CBS corporation was on a mission to scoop up any broadly entertainment-flavoured company that caught its acquisitive eye. CBS bought Fender in a deal completed in January 1965, and Leo was retained as a special consultant, stationed well away from the company buildings and with very little effect on the product. He left when his five-year contract expired in 1970, which as we’ve seen was around the time he switched his attention to the new Music Man company.

Under CBS, Fender sales increased and profits went up, but gradually it seemed that without Leo, and as the other original team members gradually left, the guitars and amps were not like they used to be. Today, the modern Fender company seems relatively healthy, and yet however much it draws on modern manufacturing advances, however much it trumpets this or that new model, much of its heart and spirit harks back to those original designs and innovations from Leo Fender’s time at the helm in the 50s and early 60s.

It’s not hard to spot Leo’s legacy. It’s right there every time you reach for a Tele or a Strat or a Precision, every time you see someone toting a Jazzmaster or a Jaguar or a Jazz Bass, or even a StingRay bass. “Leo was a wealthy man,” George Fullerton said, “and was as well known or more as many popular people, and still is today. I doubt you could go to any country on earth today and they haven’t heard of Leo Fender, and there’s probably very few other men that fits that spot.”

His second wife, Phyllis, remembered a reticent, private man. “He was really quite shy,” she told me. “And like so many geniuses, he was content to stay by himself and work in his own little world. So Leo’s social graces really weren’t wonderful. But he had a dream, and he was loyal to that dream. He just was possessed with this desire and he stayed faithful to it.”

It’s remarkable that Leo and his team got so much right in those early years of innovation and invention in Fullerton. Justin Norvell, who is an Executive Vice President at the modern Fender company, reckons that’s because Leo and his pals didn’t tread the conventional path. “They came at it from an angle of serviceability, manufacturability, and utility,” he says. “And Leo had this saying: ‘If I have 100 dollars to make something, I’ll spend 99 making it work and one dollar making it pretty.’ That was like the best spent dollar! It was the farthest a dollar’s ever gone.”