The history of the Epiphone Casino

The Epiphone Casino found its way into the hands of rock royalty at the very peak of their powers. Here’s how this much-loved model was born.

All three guitar-playing Beatles were Epiphone Casino owners. Image: Mark and Colleen Hayward / Redferns / Getty Images

With the recent launch of a made-in-USA Casino, Epiphone chose to mark an important 60th birthday in some style. The brand’s original Casino was launched in 1961 as one of the models Gibson introduced following its acquisition of Epiphone, a company based for many years in New York City.

- READ MORE: An oral history of the Fender Stratocaster

Gibson did the deal in 1957 to get at Epiphone’s successful upright bass business, with the guitar lines an afterthought that happened to come along with the brand name. In fact, the basses never went well for Gibson, and production was short-lived. As for the guitars, you only have to look around today to see how well they have gone for Gibson.

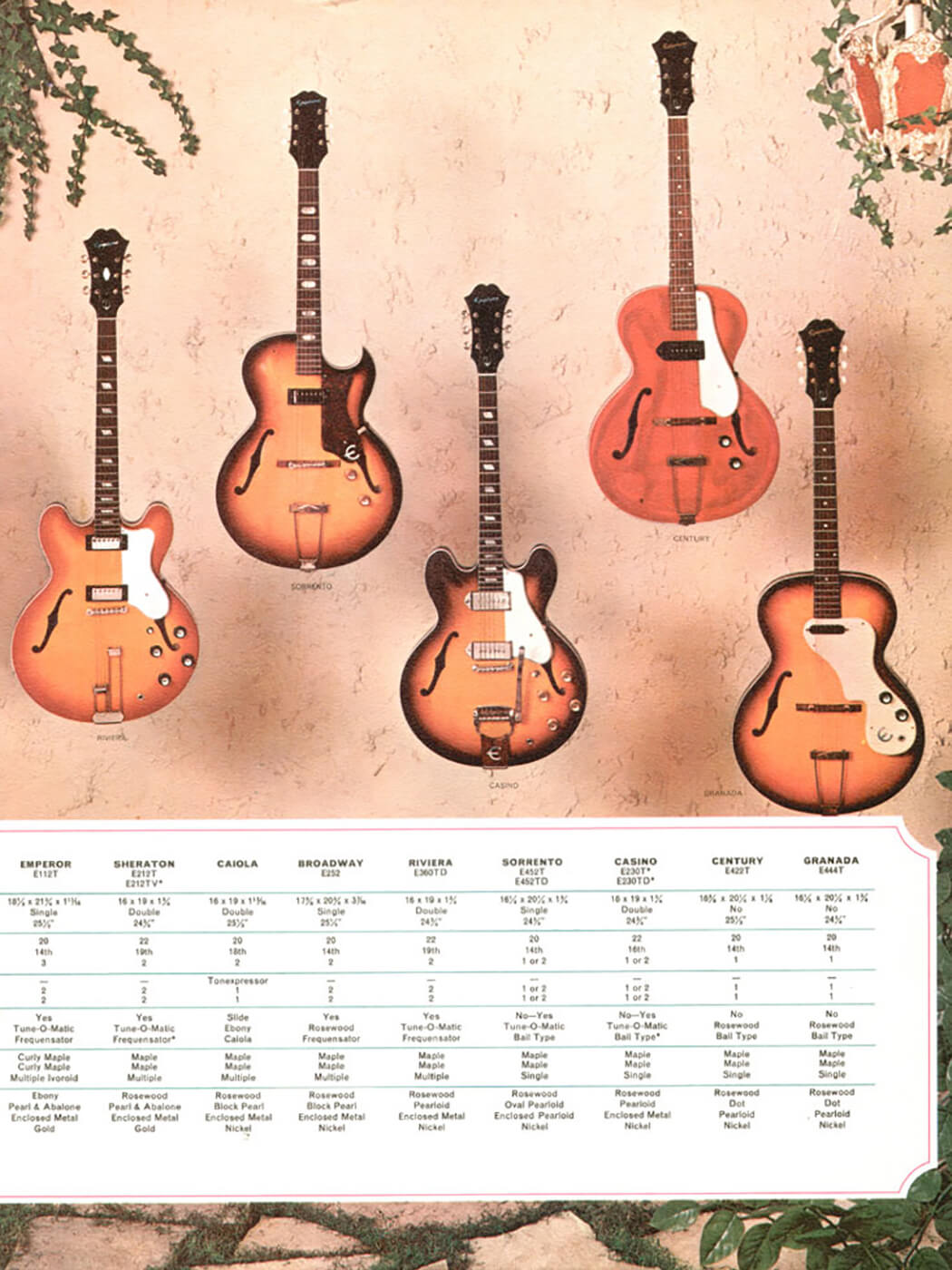

In 1958, Gibson released the first of its new Epiphone-brand guitars, which had the effect of creating an ancillary tier to the Gibson lines. Some of these ‘new’ Epiphones continued the look and intention of existing Epi models, while others were Epi near-equivalents of Gibson models, with different pickups and varied feature sets so there were still distinctions to separate the two brands. The Epiphone Casino fell into the second category and went into the catalogue alongside the similar if high-end Epiphone Sheraton, which had been introduced in 1959.

Gibson had recently introduced the ES-335, its groundbreaking semi-solid double-cutaway thinline electric, and in the wake of its success the company’s bosses created a series around it, adding a few more models in the same style. These were the stereo 345 and the high-end 355, and also a full hollowbody version, the ES-330. They were quick to apply some of these approaches and ideas to the new Epiphone lines.

Epiphone’s semi-solid Sheraton (originally intended to be called the Deluxe) was roughly equivalent to the Gibson ES-355 in its fancy appointments, while the Casino was a close relation to Gibson’s hollow 330. The Sheraton remained as the only semi-solid among the Gibson-made Epiphones until it was joined in ’62 by the Riviera, which broadly corresponded to the 335.

To understand how Gibson positioned the new Casino in its revised and reworked Epiphone range, let’s briefly consider the ES-330. The 330 was available at first with one or two pickups, and the October/November 1959 issue of Gibson’s Gazette promo magazine announced the pair as “beautiful professional-type guitars, economy priced by Gibson”. The blurb said they replaced the single-pickup thinline ES-225T, explaining why – for a while, at least – the 330 came in those single or double-pickup versions.

A further difference between the 330 and the semi-solid models was that the 330’s neck was fitted further into the body. Unlike the 335, 345, and 355, the 330 had no solid block inside the body. As a result of the different fit, the 330’s neck joined the body around the 16th fret. The ES-330 had a regular hollowbody-style trapeze tailpiece, plus that choice of one or two single-coil P-90s, with two or four controls as appropriate. The single-pickup version didn’t last long and was dropped in ’63.

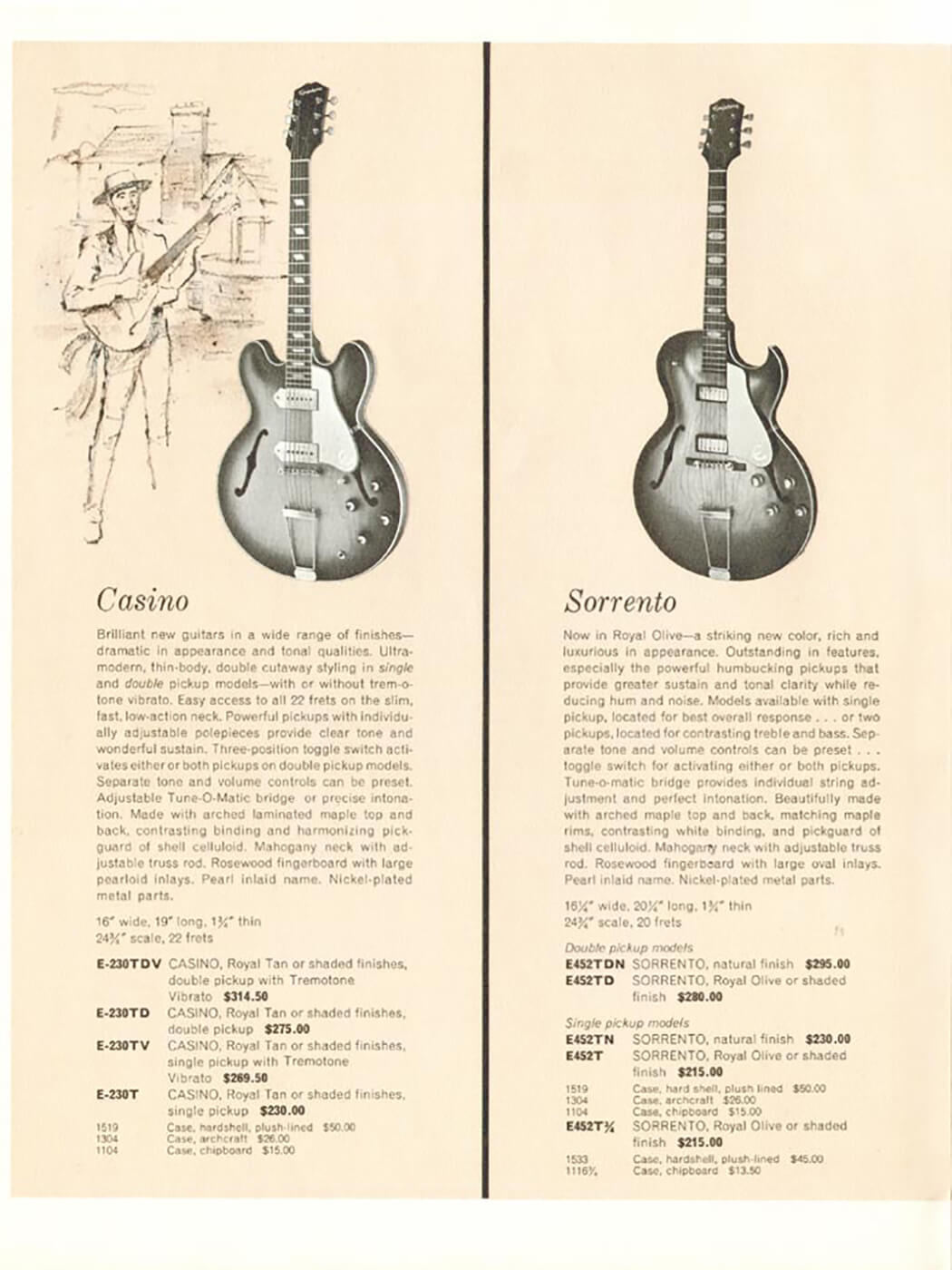

Right, let’s get back to the Casino. When the first examples were shipped from the Gibson factory in Kalamazoo, Michigan, in 1961, the basic specs were all in place. Epiphone’s catalogue from that year trumpeted the Casino as having “ultra-modern, thin-body, double cutaway styling”. List prices for the single-pickup model were $230, or $269.50 with vibrato, and for the two-pickup model $275, or $314.50 with vibrato.

The body was about 16 inches at its widest and around an inch and three-quarters deep, and it had a pressed three-ply laminated top, back, and sides – maple for the two outer plies plus a softer inner ply, often poplar. Gibson used specialised presses to contour and arch the Casino’s laminated tops and backs and to shape the sides. This Epi body had the twin 335-style rounded cutaways, in this case leaving 16 frets clear of the body.

What the catalogue went on to call the “slim, fast low action neck” was one-piece mahogany, glued to the body with Gibson’s standard mortise-and-tenon joint. A rosewood fingerboard was glued to the neck over a strengthening truss-rod in its slot in the neck, and the scale-length was Gibson’s regular 24 3/4 inches.

Dot position markers were inlaid into the single-bound fingerboard, which had 22 frets, and there was a hard plastic nut at the top. Six Kluson Deluxe tuners were fitted to the headstock, each with a closed back and plastic oval button, and a plain black-topped plastic plate on the headstock covered the truss-rod adjustment point.

There were two finish options upon launch. One was called “royal tan”, an attractively pale orange-yellow sunburst, coupled with red-brown sides, and the second was the more traditional looking “shaded”, essentially a dark sunburst, with dark sides. There was single white plastic binding glued to the top and back edges of the body, and two traditional f-holes cut into the top.

Visible through the controls-side f-hole was Epiphone’s pale blue label indicating ‘Style’ (Casino Dbl for two-pickup or Sgl for one-pickup), Epiphone model number (E-230TD for two-pickup thinline double or E-230T for single-pickup thinline), and ‘No.’ (serial number – “guarantee void if number is defaced”).

The nickel-plated metalwork on the Casino included two strap-buttons at the neck heel and at the back edge of the body. Below the pickups was the pickguard, fixed to the body with two screws, one at the neck and another fixed to a metal bracket that was in turn screwed to the side of the body.

The bridge was a Gibson Tune-o-matic, and two P-90 pickups with black plastic dogear covers were in the regular neck and bridge locations. The optional single-pickup version had its P-90 centrally positioned. On the two-pickup model, standard Gibson wiring meant four 0-to-10 bonnet control knobs and a three-way switch with white tip in front of them, or just two knobs on the single-pickup variant, and of course both versions had a metal output socket to the rear of the controls.

“George and John had the sunburst finish stripped from their Casinos. George said he thought this improved the sound”

Epiphone made changes through the Casino’s first era, which lasted from its introduction in 1961 until 1970. For example, some early examples had Epiphone’s older metal curving triangular badge at the headstock, but soon a pearloid Epiphone logo was in place at the tip. Also evident on some early examples was a tortoise pickguard (which Epiphone called “shell celluloid”), but soon the model settled on a three-ply white-topped guard, both inlaid with the brand’s wonderfully stylish ‘E’ logo. At first there were options of a regular trapeze, or Epiphone’s basic Tremotone vibrato tailpiece (“for pulsating effects” according to the ’61 brochure), and sometimes Epi’s Frequensator two-pronged tailpiece or a factory-fitted Bigsby.

Around the end of 1962, the fingerboard inlays were changed from dots to offset diamonds (or “single parallelograms” in Gibson-speak), and the pickup covers were changed from black plastic to nickel-plated metal around ’63. Another finish option arrived in 1967 when cherry replaced royal tan, and around the same time the single-pickup variant was dropped, resulting in revised model suffixes: E-230TDVC thin body, double pickups, vibrato, cherry; E-230TDV thin body, double pickups, vibrato, shaded; E-230TDC thin body, double pickups, trapeze, cherry; and E-230TD thin body, double pickups, shaded.

According to Gibson’s shipping records, the best year for the Casino in terms of sales was 1967, when a total of 1,814 left the factory, up from an early low in 1963 of 376, although the figures took a tumble after 1968 to 140 in ’69 and just 11 in the first era’s final year, 1970. It’s hard to resist the conclusion that the doubling of sales from 1965 (853) to 1966 (1,655) was down to the Beatles effect, because in 1966 the band played their final tour dates – including the very last Beatles concert in San Francisco that August – with George and John each brandishing a Casino as their main stage guitar.

The Beatles–Casino liaison had begun at the end of 1964, when Paul – remember he started out in the band as a guitarist – bought himself a Casino, which he restrung and played ‘upside down’ to accommodate his left-handed style. He recalled later that a discussion with John Mayall influenced his decision to get the Epi. The year after Paul’s acquisition, John and George bought their Casinos, and all three used them on the sessions for Revolver.

Paul’s ’62 model had the black knobs and Gibson-style headstock of the period, plus a Bigsby, while John and George’s ’65 models had gold knobs and Epi’s later flared-style head. George’s came with a Bigsby, John’s with the regular trapeze tailpiece. Later, George and John had the sunburst finish stripped from their Casinos to reveal the natural wood, and George said later he thought this improved the sound.

After its original demise in 1970, the Casino reappeared later, at first as part of Epi’s Japanese-made lines in the 80s, and then more recently in many reissues, revisions, and signature models, including a good number of Beatle-related models. In its 60s heyday, however, it was a strong member of the Gibson-made Epi range, living up to the proud description in the launch-year catalogue, where the Epiphone Casino was hailed as a “brilliant new guitar… dramatic in appearance and tonal qualities”.

For more guides, click here.