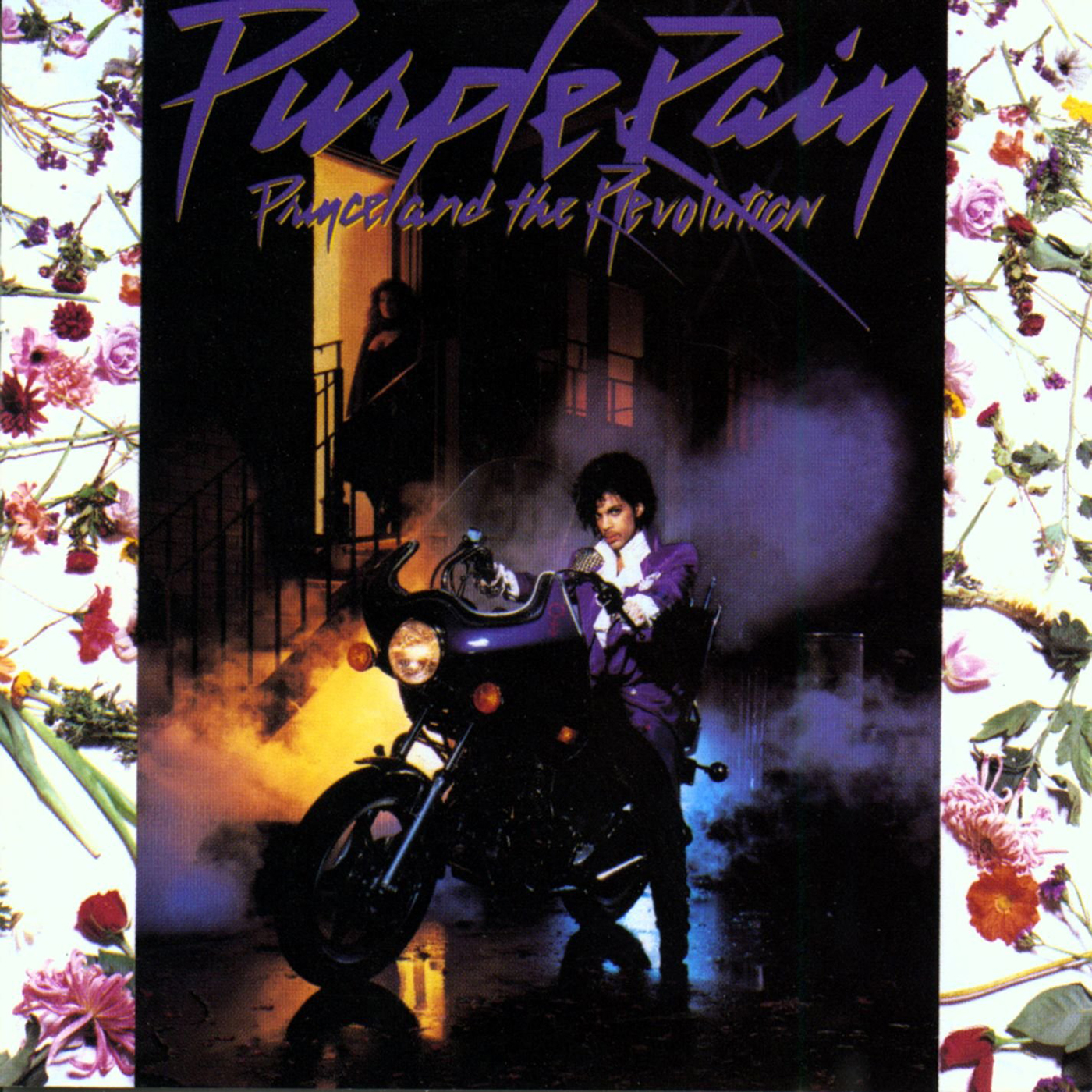

The Genius Of… Purple Rain by Prince and The Revolution

Prince’s 1984 triumph decimated genre barriers with a diverse mixture of instrumental flavours, it would also verify its creator’s position among the most gifted guitar soloists of all time.

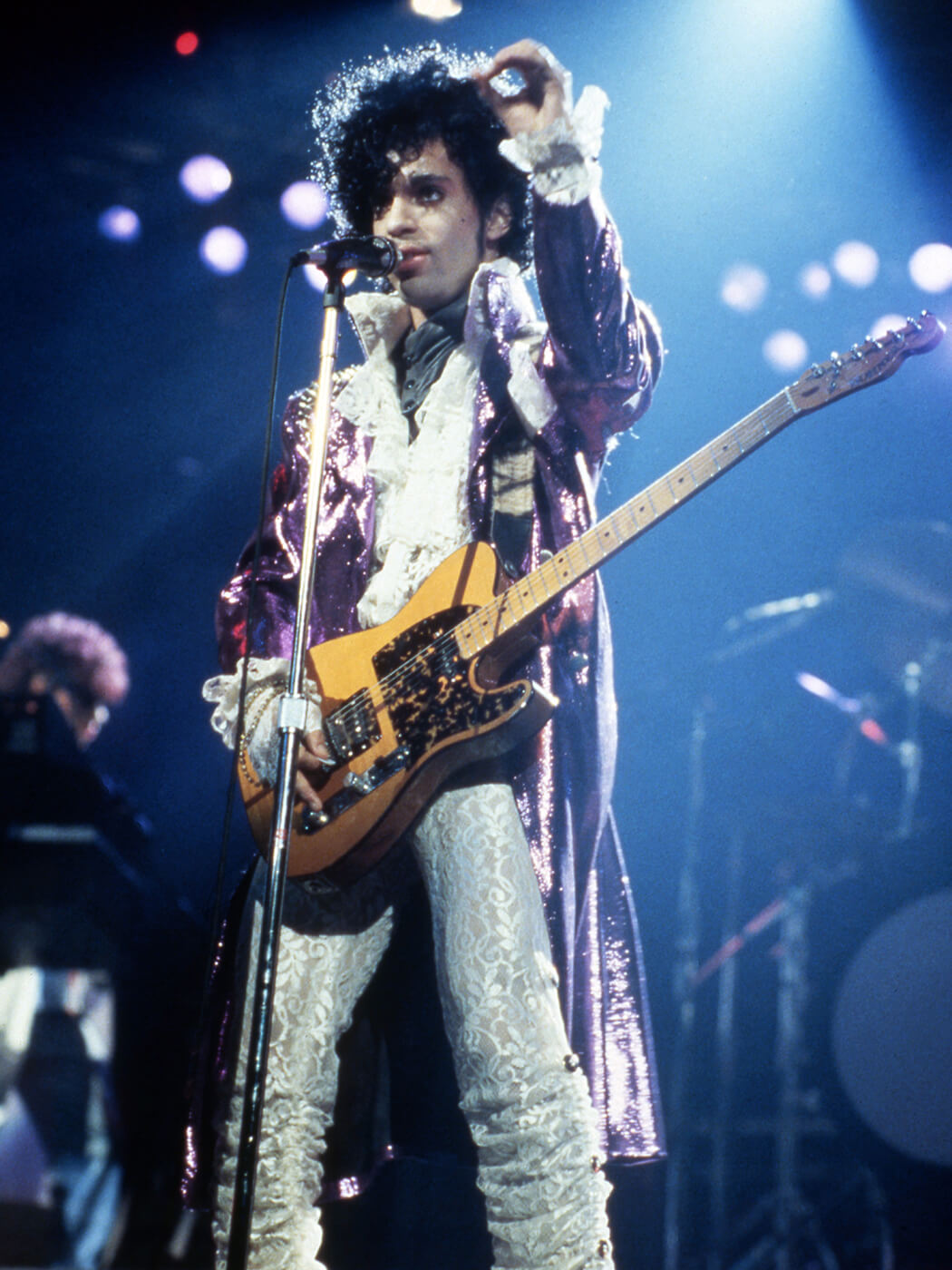

Image: Ross Marino / Getty Images

“Dearly beloved, we are gathered here today to get through this thing called life.” Exclaims Prince in the sermon that begins Let’s Go Crazy, the opening cut of his momentous sixth studio record. It’s a statement that affirms Purple Rain’s intentions outright – this is a nine-track document of a life’s adventure, a eulogy for lost loves and paths not taken, and an artistic venture intended to make sense of an extraordinary, near-supernatural metamorphosis from humble beginnings up to the very pinnacle of pop supremacy. With Purple Rain, Prince was both reflecting – and putting his foot harder on the accelerator pedal – on his journey towards pop cultural demigod.

Released ahead of a capably made semi-autobiographical movie of the same name (starring Prince as ‘The Kid’), Purple Rain seized the public consciousness like no other Prince album before it. It could even be said, that the Purple Rain era achieved a level of mixed media penetration not seen since the era of The Beatles, with both film and album sitting pretty at the top of their respective charts, and the man himself revelling in an immense celebrity.

The true power of Purple Rain lay in the vitality of its songwriting, as well as the many off-the-wall production choices – with Prince and his band, The Revolution, displaying an abject disregard for instrumental conventions, blurring any attempt at defining their music by shading arrangements with elements of R&B, pop, heavy rock, country, classical and even proto-hip-hop, all swirling together in one sonic cauldron. It’s testament to Prince and his band, the Revolution’s finesse, that these disparate elements came together so well.

Prince had already proved himself an exceptional guitarist, but in Purple Rain’s jubilant context, the smoldering power of his passion-led soloing entranced all, and mirrored the transformative through-line of the album’s theme. From the darting uncertainty of the carousel thrill of Let’s Go Crazy, via the hurricane of fiery fuzz at the core of The Beautiful Ones, the Western-like, ‘arrival’ cue that introduces the majestic When Doves Cry, to that monumental, tear-jerking solo at the album’s grand finale – a masterclass in lead guitar is delivered, with Prince’s deep understanding of dynamics informing his more flamboyant fret-flights by tactfully restraining himself elsewhere.

This is what it sounds like

Like many artists, Prince’s gradual ascent to success had been slow, turbulent and marked by unrealised expectations. From a young age, the Minneapolis-born Prince Rogers Nelson’ parents (who would divorce when he was aged ten) instilled in him the value of music, particularly his jazz musician father, John Lewis Nelson who bestowed his own stage name, Prince, upon the child. Developing into a capable musician and songwriter, Prince’s early output – across the four albums; For You, Prince. Dirty Mind and Controversy – had found him erratically attempting to carve out a distinct musical niche, with mixed results. For those tuned into Prince’s expanding sound palette however, the development from the precarious funk/R&B of early tracks such as For You’s Baby to the much more innovative track construction that peppered Dirty Mind and Controversy was a strong indicator that this was a prolific, original writer who was continually striving to better himself.

Prince’s fifth album, the sprawling 1999 was his first major success, peaking at No. 9 on the Billboard chart. It also marked the moment when Prince stopped trying to painstakingly control every millisecond of sound in the studio, as he had been before. Guitarist Dez Dickerson (who left Prince’s band ahead of work on Purple Rain beginning), remembered that “He did everything himself at the beginning – that’s what Warner Brothers signed, this teen wunderkind, the next Stevie Wonder. But he also wanted to have a band, and we spent so much time rehearsing and jamming, that he felt comfortable moving away from that do-everything-yourself template.” Dickerson related to the Chicago Tribune.

Building on the success that 1999 had afforded – particularly by its trailblazing singles 1999 and Little Red Corvette – Prince set his sights on a much grander project, with his cabal of fixed musicians now defined as ‘The Revolution’. This line-up of instrumentalists included Matt Fink on synths, Brown Mark on bass, Bobby Z on drums, Lisa Coleman on keys and, filling the vacant guitarist role, Coleman’s girlfriend Wendy Melvoin. “None of us were the virtuosos that he had towards the end of his life.” Melvoin reflected with Billboard. “We were the musicians that would play one note and one note well. We became the freight train, which makes for a better band, and he could feel safe knowing we were happy to give him exactly what he wanted from each of us.”

To realise his audacious next step, Prince and the Revolution constructed a soundstage and recording studio in a warehouse on Highway 7 in Minneapolis’ suburb, St Louis Park. With the success of 1999 (and a deft feat of negotiation with his management) spurring Prince to put into motion work on the film he’d always itched to make. “I really wanted to chronicle the life I was living at the time, which was in an area that had a lot of great talent and a lot of rivalries. So I wanted to chronicle that vibe of my life.” Prince remembered in an interview with Larry King.

Hand tough children

It was clear from the outset that the vibrant sound of the record would be achieved via a smorgasbord of instruments, with a Linn LM-1 drum machine as its fulcrum, Prince decided to make the guitar adopt a more rock-like position as a spotlight-stealing focus.

Prince’s trusty maple Hohner ‘Mad Cat’ Telecaster was central to the writing and recording sessions for the album; it’s a guitar that he’d continue to use for decades. His lead parts were typically output through a Mesa/Boogie Mark IIB, with his fired-up overdrive achieved with a light application of a Boss DS-1.

Tasked with providing buoyant funk licks and shimmering chord washes, Melvoin used her Rickenbacker 330 as the main rhythm guitar, with a typical signal chain including a Boss CS-1 Compressor, and occasional TC Electronic distortion, also output through a Mesa/Boogie Mark II.

The new guitarist also impacted Prince’s songwriting process from the get-go, as she recalled in an interview with Classic Pop “Lisa and I were definitely instrumental in influencing him at that time. We were close to him and became this triumvirate. We introduced him to a lot of ideas and different kinds of music.” In the same interview, Coleman remembered that; “Wendy came up with some amazing guitar lines and beautiful chords that were indicative of the whole album. We’d all just look at each other and know where things would happen instinctively.”

Though the guitar had a meaner edge, precision was taken to emphasise its punch and service to the song as a whole. For synth-dominated, spritely opener Let’s Go Crazy the guitar takes a relative backseat for the verses, with Melvoin’s machine-like heavy metal-esque riff on F♯ working as a tempestuous cushion. At close to three minutes, Prince is given the green light to let rip, unfurling a vivid riff which catwalk struts around the arrangement, before developing into a sole dizzying runaround the key of B major, devolving into high-register squeals accentuated by his Coloursound Wah. Prince’s opening flourish is cemented by some harder edged riffage at the song’s end. Anyone doubting the man’s fretboard chops had been rendered speechless.

His creativity with the instrument was foregrounded on the overtly sleazy Darling Nikki, with its cavorting guitar part playfully reacting to its provocative lyric – grinding and squirming in suitably arousing fashion. The whirlwind guitar intro and weaving lead part of key single – and catchiest cut – When Doves Cry (also defined by its fascinatingly unique bass-free arrangement) underscores its centrality to the narrative; with an octave pedal adding greater weight to the rapid-fire riffery.

Originating from an in-studio jam, Computer Blue, became another exemplary showcase of Prince’s otherworldly capabilities; its sublime lead lick building out into a transcendent solo that required phenomenal finger-strength, with rip-roaring unison bends, harmonic scale runs and shrieking high note sustain. “The triplet guitar solo part is, interestingly enough, my albatross!” Wendy told Premier Guitar, “Every musician has their muscle memory and that lick is just Prince’s on perfect display. It was a part that he played so naturally. My muscle memory just doesn’t have the same freedom as his did, and that was just a part that came to him so easily.”

Bring a brolly

The title track’s wistful chord progression – B♭sus2, Gm11, F, E♭9 – had been dabbled with throughout soundchecks on the 1999 tour, but, in search of his epic finale, Prince re-worked the sequence into the foundation for the record’s towering parting cut, with a little augmentation from Melvoin; “I started playing this chord, and then we tried to change the chord, and Prince’s chords at the time were much more simple then. We kept all those suspended chords in there, then I put the 9 in there.” Melvoin was quoted as saying in Prince and the Purple Rain Era Studio Sessions. Framing a superb lyric which painted a picture of a couple holding firm against an oncoming apocalypse, the song’s suitably cinematic arrangement was a perfect example of the collaborative strength of the unit.

This majestic feat of songwriting concludes with an earth-shattering solo that is widely considered one of the finest in history. Bounding out of the arrangement like an uncaged animal, Prince ascends the fretboard with slick sophistication, and repeatedly returns to a heartbreakingly four-note riff.

The album version of Purple Rain was recorded live (albeit for a handful of string overdubs) along with dance-able future single I Would Die 4 U and the driving Baby I’m A Star at a now-legendary gig at Minnesota Dance Theatre at First Avenue on 3rd August 1983. Becoming an instant classic almost from its first performance, Purple Rain would become Prince’s signature, and most beloved, song

Cloud 9

During the making of the Purple Rain record and film, Prince envisioned wielding a new guitar with a design that reflected his evolution into a supernatural musical magician. Inspired by a design he’d seen on a bass played by his former bassist André Cymone, Prince commissioned Minneapolis-based luthier Dave Rusan the task of creating his new axe. “His main requirements were just that the guitar should be in that shape, and it had to be white, and it had to have gold hardware.” Rusan told Premier Guitar, “I think he specified he wanted EMG pickups, but compared to all the conversations you would have with somebody about a custom guitar, there wasn’t anything else he wanted to talk about—the size of the neck, the frets, the playability features, or anything.”

Prince was besotted with his new, soon to be iconic, instrument. Dubbing it ‘The Cloud’, Prince would use it prominently in both film and on stage for the rest of his career, with Schecter replicating the model for him many times down the line. “I’d never made a neck-through-body guitar or done anything involving that much carving.” Rusan reflected, “So I thought I’d take a shot, because I knew I’d always regret it if somebody else did it.”

A perfect picture

Released on 25 June 1984, Purple Rain would sell more than 25 million copies – buoyed by the simultaneous release namesake film. It became the soundtrack to a year that marked Prince’s absolute apex.

Though its heady mix of infectious, high-energy pop cuts appealed to listeners across the chart-buying spectrum, when those more ‘serious’ musos heard the inescapable record for the first time, and Prince’s exceptional instrumental skills, those who had rarely given the artist a passing thought before suddenly started paying very, very close attention.

This was just the beginning of course, with a whopping 33 studio albums following in its wake, including the equally as fantastic Parade and Sign O’ The Times: further evidence of his rare genius. But, it’s Purple Rain that endures the most brightly out of his canon – discovered anew by continuing generations of listeners, particularly since Prince’s tragic death in 2016. Why has its prismatic exuberance stood the test of time so well? Prince had a theory, as he told CNN; “One of the reasons for that is that I never wanted to fit in with my music. Whatever the trend was, I usually went in the opposite direction.”

Infobox

Prince, Purple Rain (Warner Bros, 1984)

Credits

- Prince – Lead Guitar, Vocals, Piano and assorted instruments, Production

- Wendy Melvoin – Rhythm Guitar, Vocals

- Lisa Coleman – Keyboards and Vocals

- Matt Fink – Keyboards and Vocals

- Brown Mark – Bass

- Bobby Z – Drums and Percussion

Standout guitar moment

Purple Rain

For more reviews, click here.